‘You don’t belong here’: Racism in youth hockey league shows hurdles facing Black players

The first time a racist taunt was directed at Brandon Bernard from the opposing team during a youth hockey game was bad enough.

Players screeched monkey noises when Bernard skated past the benches or controlled the puck.

Five times. Recorded on video.

Two months later, on March 6, came another taunt from the same team at a game in Ashburn, Virginia. A member of the Ashburn Xtreme skated up to Bernard and called him a “n—–.” Instead of retaliating, Bernard went to the referee, just like his father, Lionel Bernard, told him to do.

Yet the Xtreme never publicly took any action against members of the 14-and-under team. When USA Hockey opened an investigation several days later, the Bernards hoped for a quick and decisive ruling.

USA Hockey ultimately suspended Xtreme coach Karl Huber for 10 games, hockey director Troy MacCormick for five games and an unnamed player for three games. But the Bernards and the coach of their sons’ team, the Frederick (Maryland) Freeze, were not satisfied.

They didn’t learn of any formal discipline until more than a month later, and said the suspensions did not go far enough, failing to publicly censure the club or discipline other players who were involved.

Now Brandon Bernard and his twin brother Landon, a goaltender on the Freeze, say they feel isolated by their league and USA Hockey. But in a sport that has a long reputation for being unwelcoming to people of color, the Bernards are also finding support in unexpected places.

“I don’t think the game is as fun, as pure, as awesome, honestly, as it should be if everyone can’t enjoy it,” said Duante’ Abercrombie, a member of the Washington Capitals’ Black Hockey Committee, founded this year and comprising community leaders who work to address racism and grow the game in under-served communities.

“There’s an air of ‘you don’t belong here,’ ” Abercrombie said, “that still is in many rinks in America.”

An ugly moment

Meredith Wivell, team manager for the Freeze, was working the scoreboard on Jan. 9 when the team played the Xtreme, and she heard monkey sounds coming from their bench during the second period.

Wivell alerted the officials and Huber but no action was taken, Freeze coach Mike Gregorio told USA TODAY Sports.

LiveBarn, a video company that produces online broadcasts of amateur and youth sports from various venues, had a feed running during the game. “You better hope to God that doesn’t show anything,” Gregorio recalled telling Huber.

It did, though, as the monkey sounds were audible on five occasions. Gregorio downloaded 30-second clips of each incident and sent them to Frederick hockey director Tommy Demers.

Demers told USA TODAY Sports he contacted his Ashburn counterpart, MacCormick, who asked if there was video of the slurs. Demers told them there was but didn’t provide it. Nevertheless, MacCormick told him the incident would be handled internally.

Gregorio tried to confirm any discipline but discovered that no Ashburn player had been listed as scratched or suspended in lineups filed with USA Hockey, the national governing body for amateur hockey.

“We know somebody at the other club they played the next game, nobody scratched,” Gregorio said. “So we know nothing was done.”

MacCormick declined comment when contacted by USA TODAY Sports, and Huber did not respond to emails. The Xtreme had a statement on their website that said, “There has been an allegation of racism raised against a player in our club,” but it has been removed.

Brandon Bernard said he didn’t think anything of the noises at first. He thought the Xtreme were randomly chanting. But when Wivell informed him of the nature of the taunts, “It broke me down,” Bernard said.

In hindsight, Gregorio said he wishes he’d filed a formal complaint after the first incident with the Chesapeake Bay Hockey League and USA Hockey SafeSport, which investigates abuse in the game.

‘The Talk’

Almost every Black family has “the talk.”

What to do when pulled over by a police officer. How to behave in certain white-dominant spaces.

So Lionel Bernard sat his boys down after the first incident.

“If this happens again, the first thing you should do is reach out to the referee or coach. Don’t retaliate or get upset,’ ” Bernard told his sons.

“I also told them that this is what you can expect when you’re playing a sport that has a limited number of minorities playing it,” he said. “You’re going to run across this thing. But note that you’re not the first individuals who have faced racism in sports.”

He pointed to Major League Baseball legends Jackie Robinson and Hank Aaron, both of whom faced racial abuse from fans, opponents and teammates and death threats from all over.

His father’s words were in Brandon Bernard’s mind the next time Frederick played Ashburn and an Xtreme player called him the “n-word.”

“The first thing I did when I heard it, (I) was angry, and then I calmed myself down,” Bernard recalled, “and then I ran over to the ref and was like ‘This, this, and this happened. It was so and so.’”

Since neither referee heard the slur, the game continued, but not for long. A teammate skated up to Landon Bernard in net and told him what had been said to his brother. Landon proceed to let the other team score enough goals to invoke the mercy rule as a way to escape the situation.

After the game, the referees noted the incident on the official scorecard.

With no parents allowed in the rink due to COVID-19 precautions, the Frederick group gathered under a tent outdoors in a tailgate-like atmosphere. They were in a festive mood as the team was playing in the championship game.

Although it’s usually Lionel Bernard who takes the boys to their games, his wife, Cleo, was in attendance that night. As the parents wondered why the game was running late, Wivell called her husband who was with the rest of the parents and told him what happened. He relayed it to Cleo, who walked away to compose herself.

“Imagine that’s how the kids ended their season,” Cleo said. “All sad and stuff.”

Racism won’t be tolerated

When Abercrombie first heard about the incident involving the Bernards, he said he nearly pulled over his car to vomit.

“(Hockey) is a very exclusive sport sometimes,” said Abercrombie, who is an assistant coach for the men’s hockey team at Division III Stevenson.

More than nine out of every 10 players in the NHL are white, according to the data analysis website FiveThirtyEight, and more than three-quarters of NHL fans are white, per a FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos poll from May 2020.

The majority of racist incidents that take place on the ice are not made public or not reported through the proper channels, Abercrombie said.

Tammi Lynch is a special educator in Maryland and co-founded Players Against Hate, which aims to remove racism from hockey by educating younger players. She is trying to address those unreported incidents and collect data around them. Players Against Hate now has a tool that allows people to confidentially report alleged incidents and provide updates regarding potential investigations, discipline and solutions.

But it’s not just about acknowledgment and punishment. To that end, Players Against Hate is developing a curriculum Lynch is hoping to pilot this year – with the help of the Capitals – that teaches players, coaches, parents and officials that racism won’t be tolerated.

“We want to educate to eradicate racism,” Abercrombie said. “Of course, the individual needs to be suspended, because they’ve shown they’re not mature enough to be a part of competition or USA Hockey at the moment. So, suspend their ability to participate, but don’t just cut them off. You have to rehabilitate, so to speak, so that this doesn’t happen again and, honestly, so this individual becomes an advocate for race relations in the future.”

Part of the discipline doled out to Ashburn, USA Hockey said, will include educational training at the recommendations of the organization’s director of diversity and inclusion, Stephanie Jackson.

One tactic to combat on-ice racism in the future, Lynch described, could look like this: If an incident happens during a game, stop the contest, announce to the rink what has allegedly happened and why it’s being reported, and have a conversation about how those actions aren’t tolerated.

“You nip it in the bud and do that, but there still has to be official guidelines,” she said. “And that’s one of the things that as an organization we’re still working on.”

The Bernards would like a more public statement condemning the actions along with the discipline being formally announced. And, Cleo Bernard added, more than one player should be suspended on the account of the multiple players making monkey noises during the first incident.

“I personally have not seen change that has come of (investigations in general),” Lynch said. “And as a hockey mom, and seeing what’s happening, I don’t see a change that’s coming. I see that there’s situations where the victim or the target is blamed, where maybe a person is not believed. In conversations that I have with people, some of what I’m seeing in the reports, is that nothing is done and nothing has happened.”

Seen like any other player

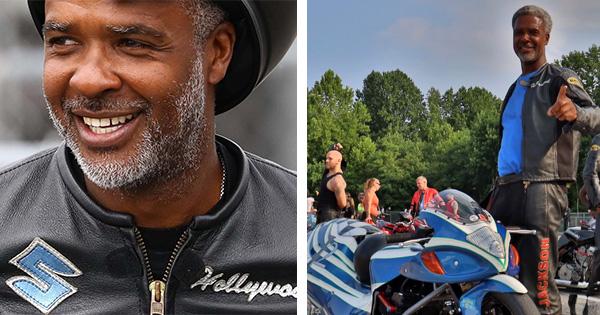

The Bernard brothers have heard from many supporters throughout this ordeal. The Hockey Players of Color Movement, a group composed of players of color who mentor youth players, made a video that addressed the twins directly and encouraged them to not let the experiences stain their passion for the game. But Brandon Bernard said he thinks Abercrombie was the ideal person to offer guidance.

“It was almost like I was talking to an older version of myself because he had the same exact experiences as us,” he said.

Both twins wear glasses; Brandon with black rims, Landon’s white. As a forward-goalie tandem, practicing with each other is easy. Sometimes they’ll throw the pads on for a garage session if they don’t feel like going to a nearby rink.

Prior to these incidents, Brandon said, the Bernards hadn’t experienced explicit racism on the ice aside from the typical microaggressions, such as a player skipping them in the post-game handshake line.

“Never thought anything about it,” he said.

The more Lionel Bernard reflects on his sons’ experiences, the more he believes they can serve as an example to others on how to best handle racism on the ice.

“When you’re this age, you’re very sensitive. As an adult, if someone does those things to you, you can deal with it, you can process it,” said Lionel, who immigrated to the United States from Liberia in 1986. (Cleo also arrived from Liberia 12 years later.) “But at this age, it gives them the impression they’re not wanted. They’re very peer-sensitive. If their peers start talking to them this way, then that gives them the impression, ‘OK, I don’t want to play this sport anymore.’

“Our goal primarily is to make sure that this doesn’t happen to other kids on the ice which leads them to quit or feel some sort of insecurity about themselves in the long-term,” he added.

And that’s why the Bernards sat on the videos with the monkey noises for months before going public with their story. They feared it would be a distraction and that other players may retaliate.

Landon, the quieter twin, is already on a pre-engineering track at Seneca Valley High School. Brandon, who plays striker for the school soccer team, is more of the reading and writing type — a future lawyer, Lionel predicts.

“I want to be defined by my personality, and what I show,” Landon said. “Not just the way I look, or my skin color.”

“I couldn’t say it any better,” Brandon said. “How I treat my teammates. My game, too. I just want to be seen as another player.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black youth hockey players face racism, slurs: ‘You don’t belong here’