Why Can’t America Address Its History?

Written by Melissa Ridge

The recent attacks against schools in Virginia—targeting everything from masks to library books to equity—are calculated and carefully scripted, and the intent is to disrupt and distract.

They are a deliberate response to the push for systemic change in our government, our judicial system, and our schools.

Over the last few years, as discussions over removing Confederate statues and memorials evolved into action, Germany was often held up as a model of how a country should confront a difficult history. There are no statues honoring Hitler or other Nazi leaders. Nazi symbolism, including the flag, is barred from display by law. There is no sympathy for the “other side” or stipulation that both perspectives need to be presented without bias. It is understood and accepted that some things are evil, regardless of how they were justified.

Last week, our new governor issued executive orders that, as expected, catered to those who are fighting to preserve the same white-washed American history that was approved by the Daughters of the Confederacy. We knew those directives were coming, but seeing them in writing was still stunning. Again, we need to ask why white America struggles so much with confronting our history in comparison to Germany.

There was a Germany before the Third Reich. They had a history and a culture that preceded the Holocaust.

We have no other history.

America has never been America without racism and genocide.

From the land that we stand on, to our original laws and Constitution, to the federal buildings where our current laws are written and executed, there is no part of this nation that has existed without racism.

And acknowledging that conflicts with the traditional narrative, with the patriotic story of America. We’re (white) pioneers who risked our lives for freedom. We’re gritty, determined, noble, brave, “young, scrappy, and hungry,” and committed to this experiment of building a nation rooted in liberty and justice, where a man can be anything.

If we acknowledge that America was built on top of others and depended on widespread genocide and human enslavement, we will be forced to examine the most basic foundations of this country and question the history we’ve been spoon-fed since preschool.

I remember singing in first grade, “First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen. That is the story of Washington, that is the glory of Washington. In word, in deed, we’ll follow the lead of the Father of the land we love.”

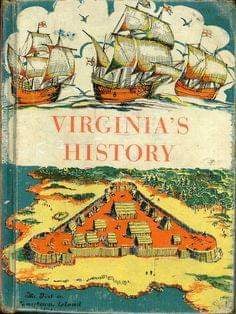

The same lyrics were in an old Virginia history textbook I found recently, buried among familiar musings about George Washington’s brilliance and leadership, and his benevolent treatment of “servants”, especially when they were ill or aging.

That textbook failed to note that the same benevolent man skirted the law when, as President, he was living in Philadelphia. The law in Pennsylvania at the time stated that any enslaved individual who had been living there for more than six months would be automatically freed. Washington would send those he enslaved either back to Mount Vernon or to just outside the state boundaries in enough time to simply start the six-month period again.

Close to twenty enslaved individuals were able to escape from Mount Vernon, but Ona Judge has gotten more attention recently as the details of Washington’s efforts to capture her have been made public. Ona Judge escaped after she learned that the Washington family planned to give her to their granddaughter as a wedding present. Washington pursued her for several years until just before his death.

Our textbooks have traditionally presented our nation’s leaders as faultless heroes, capable of creating a nearly flawless country through a combination of intellect and vision, courage, and tenacity. There’s mention of the Native Americans we shoved aside for land, but the realities of those actions have been gently buffed and polished, and their history, which is also in part our nation’s history, is ignored.

We know that, while the Founding Fathers were writing the documents that called for freedom, there were enslaved individuals doing the labor that built their homes and government offices, individuals who prepared the food that others had tended in the field, individuals who were torn from their own families in order to take care of someone else’s family.

We know that there were Founding Fathers who spoke passionately about freedom before going home and raping those who history has insisted on calling servants and who we today would call children. There are those who still romanticize Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, despite knowing that he was 44 years old, and she was an enslaved 14-year-old when their “relationship” began.

We have been okay with acknowledging those who were enslaved as a faceless collective who existed but didn’t live. It’s easy to do that because dehumanization is something America has always done well. But the faceless collective is made up of individuals who did more than simply exist. They lived. They had a history. And their history is American history. It needs to be seen and taught, not as an aside during February or as a single section in a textbook. It needs to be included simultaneously with white history. And we need to understand that, otherwise, our history is not just incomplete, but inaccurate.

The current pushback against the demand for equity and a more accurate, inclusive curriculum is not just fear of change. It’s rooted in the recognition that in teaching all of our history, in welcoming and including all American perspectives, we’re going to expose the lie behind the United States. We weren’t founded on white greatness. White men didn’t single-handedly build a nation. The original settlers were deeply flawed and often driven by greed and a belief that the people they found living here were insignificant savages. The men who wrote the founding documents wrote slavery into law. They were dependent on an industry that traded humans. Their lives and livelihood depended on the labor of those humans. There is no way to make that any prettier, and we can’t use the excuse that they were just men of their time. Some things are just evil.

In the centuries and decades that followed, the white men that led this nation continued to write laws to dehumanize the descendants of those who were enslaved by their predecessors. When the laws were overturned, white men turned to policy, tradition, and intimidation. And the history books still talked about servants and benevolent plantation owners.

Our past is ugly. We don’t have an American history that we can separate from white supremacy or from racism and genocide.

And this is the true test of American bravery and grit. We have the unique strength of diversity and perseverance. If we face our history, all of our history, and see who we were and how we got here to this moment and use the momentum of this moment to move forward without cowering from our past, we have the potential to be everything we were promised to be.

But we need the grit to do it. We aren’t responsible for the past or the systems the past created. We are responsible for how we choose to address it.

Melissa Ridge is an HBCU alumna and educator who has lived in Prince William County for three decades.