Virginia prepares to launch its first recovery high school

By the time Libbie Roberts graduated from Thomas Dale High School in Chesterfield County, she was what she described as a “full-blown addict.”

“One day, I was feeling sick,” she said. “I had the shakes, the sweats, nausea, vomiting — I thought it was the flu.” Her parents took her to the doctor, who used the opportunity to refill her depleted prescriptions. Within 15 minutes after taking the pills, Roberts started feeling better.

“That’s when I knew,” she said. “Immediately, I felt guilty and ashamed, like something was wrong with me.”

If she had known about treatment options — or if opioids had been discussed in the 1990s the same way they are today — Roberts said she might have told her family. Instead, she hid her addiction throughout high school, and eventually turned to heroin when prescription opioids became too expensive.

That experience of isolation is why Roberts, now 40, has been one of the most vocal advocates for a new recovery high school set to open in Chesterfield this August. Virginia’s latest two-year budget allocates just over $1.3 million in start-up funding for the program, a pilot that will be open to any student recovering from a substance use disorder in 11 counties around central and southern Virginia.

As a model, recovery schools have existed since the 1970s, when a few treatment centers and at least two public school districts launched educational programs specifically for students with addiction. But they’ve continued to expand across the country, especially with the advent of the opioid crisis. Andrew Finch, an associate professor at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College and co-founder of the Association of Recovery Schools, says there are currently at least 43 active recovery high schools in 21 states, with two more expected to open this year.

The Chesterfield program will be Virginia’s first, but its goals are similar to those of existing schools. Experts say the model increases the odds that teens will stay in recovery by making sure they’re surrounded by like-minded students in a supportive environment. By integrating counseling and other support into the school day, the programs aim to prevent relapse, keeping kids on track to earn their diplomas.

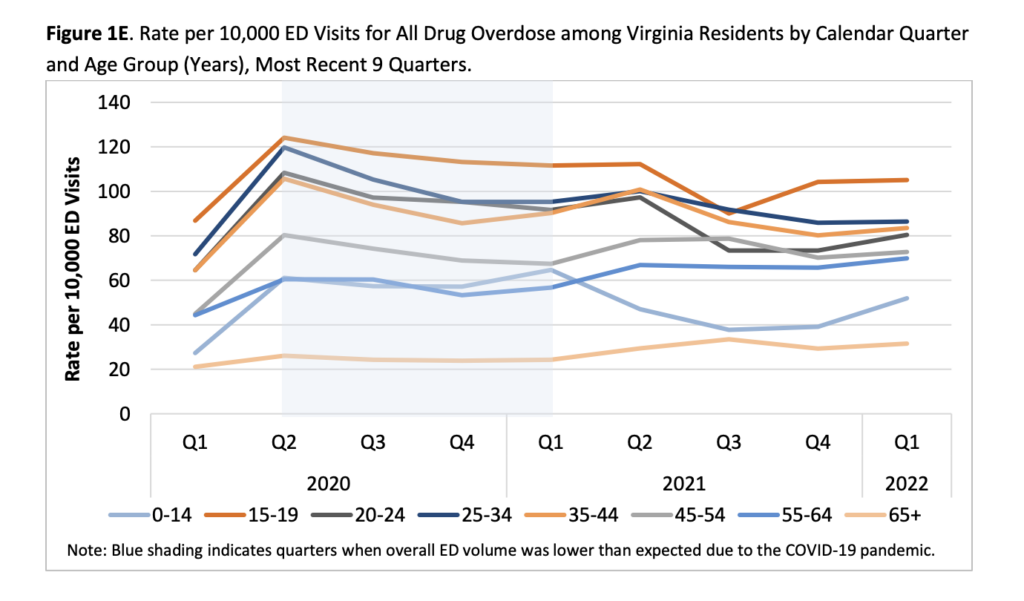

Interest in the model is growing as substance use continues to rise in Virginia. At least 38 children between the ages of 12 and 17 have died of drug overdoses since 2018, and overdose-related emergency room visits also increased by 7 percent statewide between the end of 2021 and start of 2022. For the last two years, the rate of visits for 15- to 19-year-olds has consistently been higher than that of any other age group, according to data from the Virginia Department of Health.

The push for a program in Chesterfield County was driven in part by Republican Del. Carrie Coyner, a former school board member who said she knew students who withdrew from classes to receive addiction treatment. The initiative continued under current Superintendent Mervin Daugherty, who had been working to start a recovery school in Delaware before he joined the division.

In 2020, Coyner successfully sponsored legislation that authorized Chesterfield County to establish its own program. But the funding was frozen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the initiative stalled until the money was restored this year.

While the school is set to open its doors on August 22, some details are still being fleshed out. Daugherty said the program could start with anywhere between 25 and 40 students, and the district is still in the process of hiring a teacher, a program coordinator and other administrative staff. The state’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services also contributed $299,773 for two part-time recovery specialists and three clinical staffers, who will be hired through the county’s community services board.

While there’s an expectation that students remain committed to recovery, the school won’t take a zero-tolerance approach to substance use. Daugherty said relapses will be handled on a case-by-case basis, with the goal of encouraging students to stick with the program.

“We want them to be successful, so we have to keep their needs in mind as well,” he said. “The intent has always been to be as supportive of an environment as possible.”

As the recovery school model has become more popular, more evidence has emerged on its effectiveness. Finch was one of the lead researchers on a study funded by the National Institutes of Health that compared two samples of students with substance use disorders — one with students who attended a recovery high school for at least 28 days and one with students who did not.

The last 40 years have seen multiple closures of high-profile schools, including Sobriety High — a Minnesota-based charter that once had four campuses — and Phoenix Academy, a program in Maryland often described as the first recovery high school in the country. Phoenix was ultimately folded into a larger alternative school, according to Finch, and the recovery program eventually disappeared.

That kind of slow closure is fairly common in the field. With an average enrollment that ranges from 30 to 70 students, recovery programs are more expensive to operate than larger schools. It can be challenging to accommodate the educational needs of students in different grade levels, and clinical staff adds to operating costs.

Lawmakers haven’t settled on a long-term funding plan for recovery schools in Virginia, though Coyner suggested it could look similar to how they handle governor’s schools, which are funded through a mix of state and local dollars with an additional budget add-on.

If the model takes off, it could mean a significant investment for the state. According to Coyner, Virginia Beach has reached out to Chesterfield with interest in starting its own recovery school, and Daugherty said he’s also heard from other districts looking to replicate the program.

(Editor’s Note: This article was edited and republished with permission by the Virginia Mercury.)