Things They Don’t Teach You In School: Barbara Rose Johns

“It was time that Negroes were treated equally with whites, time that they had a decent school, time for the students themselves to do something about it. There wasn’t any fear. I just thought — this is your moment. Seize it!”

These were the words spoken by Barbara Rose Johns, who took the courageous step in leading one of the Commonwealth’s biggest protests and leading the charge for change within Black and Brown schools throughout not only Virginia, but in the United States. Born in New York City in 1935, she moved to Prince Edward County, Virginia with her grandmother where she attended school while working on her family’s farm.

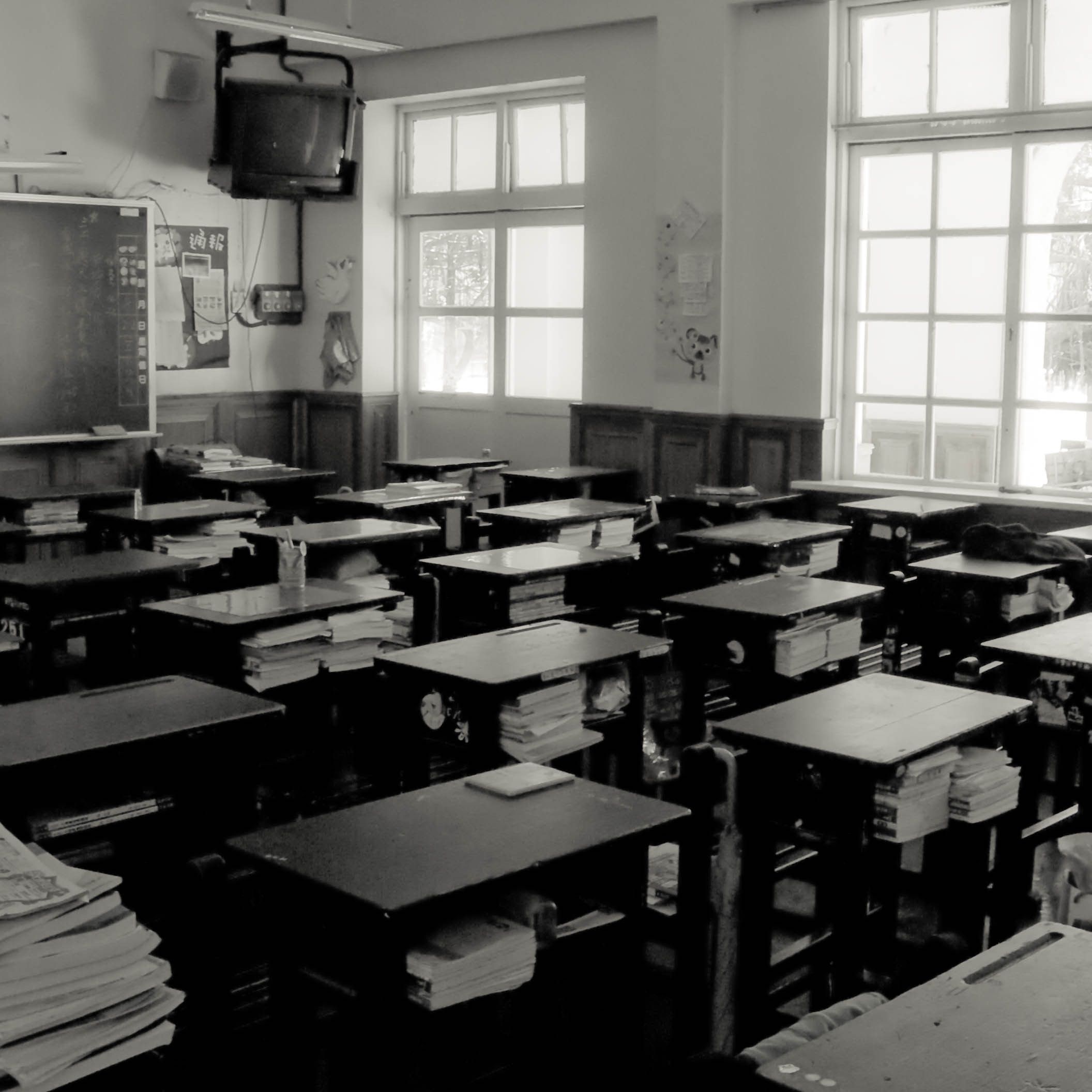

During her years at the school in Farmville she described the conditions of being “poor, inadequate and having no laboratories or gymnasium.” She recalled her teacher telling her, “Why don’t you do something about it?”

According to the Robert Russa Motom Museum in Farmville, as Barbara describes it:

“the plan I felt was divinely inspired because I hadn’t been able to think of anything until then. The plan was to assemble together the student council members…. From this, we would formulate plans to go on strike. We would make signs and I would give a speech stating our dissatisfaction and we would march out [of] the school and people would hear us and see us and understand our difficulty and would sympathize with our plight and would grant us our new school building and our teachers would be proud and the students would learn more and it would be grand….”

On April 23, 1951, Barbara Johns, a 16 year-old high school girl in Prince Edward County, Virginia, led her classmates in a strike to protest the substandard conditions at Robert Russa Moton High School. Eventually she garnered the support of NAACP lawyers Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill to take up her cause for more equitable conditions for Moton High School.

After meeting with the students and the community, Robinson and Hill filed suit at the federal courthouse in Richmond, Virginia. The case was called Davis v. Prince Edward. In 1954, the Farmville case became one of five cases that the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed in Brown v Board of Education of Topeka when it declared segregation unconstitutional.

Afterwards, Barbara was sent to live with her Uncle Vernon Johns in Montgomery, Alabama, to finish her schooling. Vernon was considered the originator of the Civil Rights Movement, later succeeded by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

On December 16, 2020, the Commission for Historical Statues in the United States Capitol, selected Johns to replace the Robert E. Lee statue in Washington D.C, after receiving public input from Virginia residents during several virtual public hearings.

“We should all be proud of this important step forward for our Commonwealth and our country,” said Governor Ralph Northam in a press release honoring Barbara’s life. “I look forward to seeing a trailblazing young woman of color represent Virginia in the U.S. Capitol, where visitors will learn about Barbara Johns’ contributions to America and be empowered to create positive change in their communities just like she did.”

The latter years of her life involved marrying Reverend William Powell, raised a family and served as a librarian in Philadelphia Public Schools until her passing in 1991.