Things They Don’t Teach Us in School: The Story of Seneca Village

When it comes to Black history and wealth, many times historians will discuss places such as Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which was known as “Black Wall Street,” due to being a place of prosperous businesses. Sadly it was destroyed by acts of racist violence in the 1920s. Before Greenwood, however, there was another place where Black people had established a community of flourishment that also met an unfortunate ending. This took place in New York City, and it was known as Seneca Village.

The following is from the National Park Service website:

In the early 1800s, the population of New York City grew very quickly. More and more, residents looked for ways to get away from the city’s growing noise and chaos. At the time, open green spaces in New York City were mostly cemeteries. People flocked to them to walk, picnic, and otherwise spend some time closer to nature. In Europe, rich people went to grand public parks like Hyde Park in London to escape the hustle and bustle. Looking to Europe, wealthy New York City citizens argued that they, too, should have a grand park.

Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux developed the winning plan for Central Park’s design. Olmstead described it as “the first real Park made in this country — a democratic development of the highest significance.” In 1853, the New York State legislature chose 750 acres of land in New York City to be the site of the new park. Located north of the developed downtown, the property ran from 59th to 106th Streets.

While largely rural, the land that the legislators chose was not empty. On it were several communities of people who had purchased the land in the very early years of the 1800s. One of these was Seneca Village. Free Blacks founded the village in 1825: the first free Black community in New York City. When slavery ended in New York State in 1827, the population grew as people built and rented homes here. The town grew to be a middle-class Black community of almost 5 acres. It had streets, three churches, two schools, and two cemeteries. More than 350 people lived in Seneca Village. As well as the Black population, German and Irish immigrants also lived in the community. Of the 13,000 Black New Yorkers, 91 were qualified to vote, and of the voting-eligible Black population, 10 lived in Seneca Village. The purchase of land by Blacks had a significant effect on their political engagement. Blacks in Seneca Village were extremely politically engaged in proportion to the rest of New York.

As the development of Central Park grew closer, newspapers and politicians began to describe the predominantly Black villages as “shantytowns.” They called the residents “denizens,” “squatters,” “vagabonds,” and “scoundrels.” Residents of Seneca Village fought to keep their homes and community intact. But in 1857, the city used eminent domain to forcibly remove them. Police removed those who resisted, and the supremacy of the law was upheld by the policeman’s bludgeons. Once the people were gone, the city demolished the village. Historians know very little about what happened to the former residents.

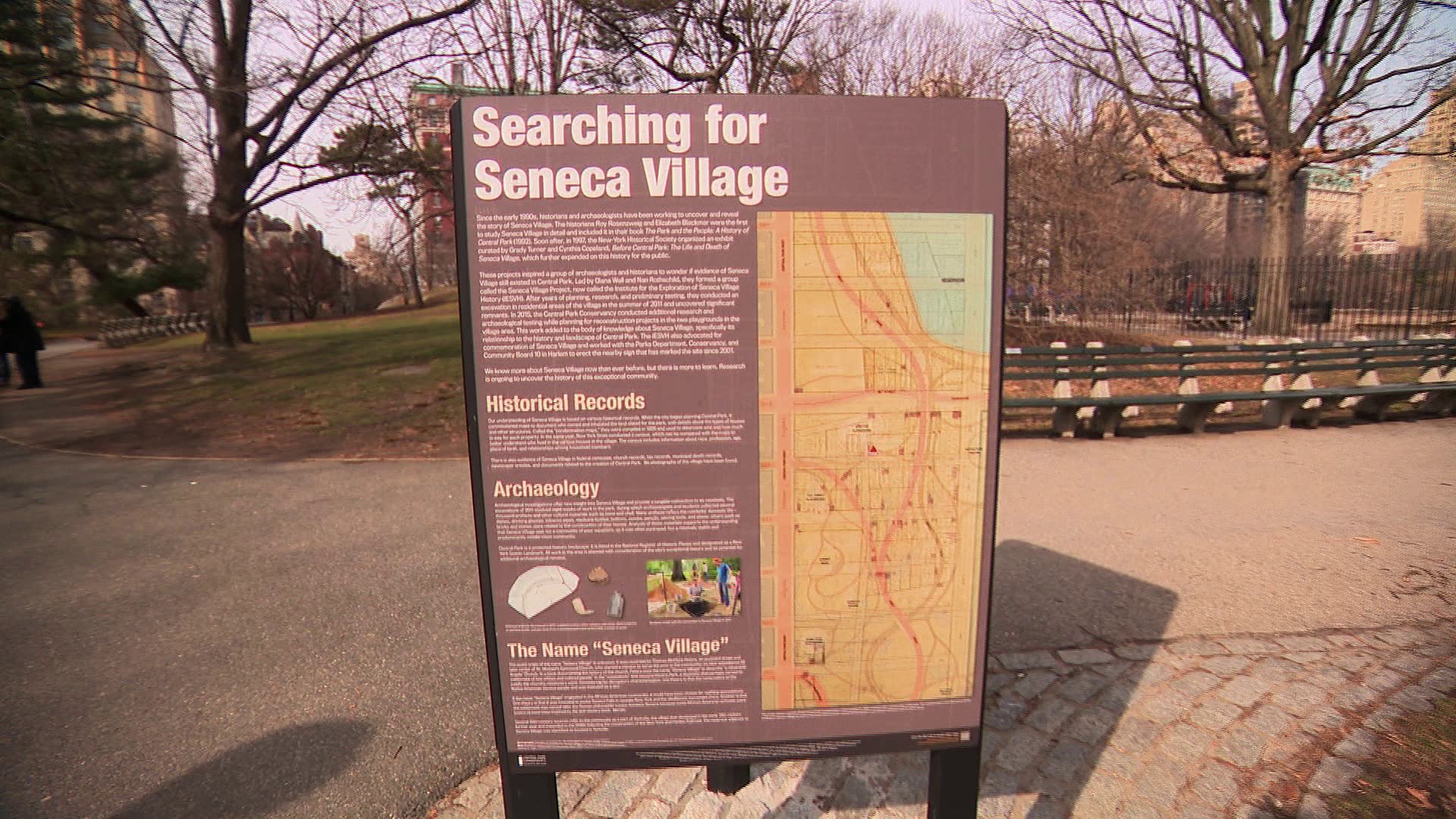

The Seneca Village Project was formed in 1998 to raise awareness of the village, and several archeological digs have been conducted. In 2001, over 140 years after Seneca Village was destroyed, an historical marker was placed at its former location.

Seneca Village is yet another reminder of how while racist acts attempt to stunt the progress of Blacks momentarily, it can never stop their determination.