Things They Don’t Teach In School: The Real Cinco De Mayo

Often when people think of May 5, otherwise known as “Cinco De Mayo,” in America it becomes remembered most for people flooding their local Tex-Mex themed restaurants for fajitas and cervezas. Before you sip that strawberry-flavored margarita, though, take a moment to reflect on what this day really means.

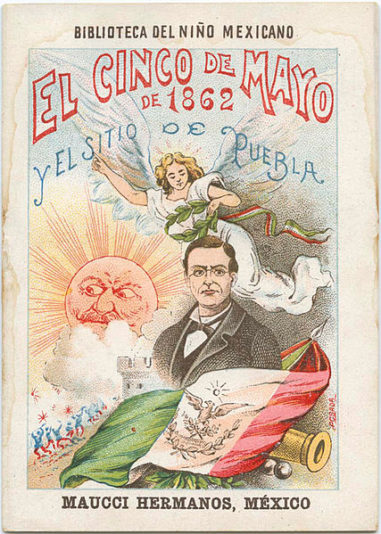

Cinco de Mayo has been celebrated in the United States more than in Mexico. Celebrations in the state of Puebla (100 miles east of Mexico City) are common, but are fairly uncommon in the rest of the country. Many Puebla residents are conversant about the 1862 battle and how naval forces from Great Britain, Spain, and France traveled to Mexico to negotiate various financial debts. Spain and England settled their conflicts and left quickly but France decided to fight, believing they would be the easy victors and could establish a French colony in Mexico. Mexican soldiers, greatly outnumbered and poorly armed, prevailed. The battle is a source of pride for many Mexicans but not necessarily a major national holiday.

Historically, El Cinco de Mayo is a U.S. holiday that originated after the Gold Rush and during the U.S. Civil War, and was celebrated in California, and to a lesser extent in Nevada and Oregon,. It was created to affirm Latina/o pride and identity and it was also a way to respond to and resist many forms of oppression, from the Foreign Miners Tax, “Greaser Law,” denial of suffrage, injustice in the courts, lynchings, and land theft by European Americans. During El Cinco de Mayo celebrations, Chicanos/as flew both the U.S. and Mexican flags to demonstrate their support for Mexicans fighting despotism by the French in Mexico and to show solidarity with people held in slavery in southern U.S. states.

During the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, activists incorporated Chicana/o interests by strengthening cultural ties between Mexico and the United States. The United States had historically looked favorably upon the Battle of Puebla because in 1862 U.S. leaders feared having France at its backdoor, during the U.S. Civil War. Thus, more than 100 years later, Cinco de Mayo was readily embraced as a new U.S.-Mexican holiday.

Sadly, like most events in America, this has turned from being a day of remembrance to a day filled with stereotypes. Throughout schools across the nation celebrations are held but it’s reduced to wearing sombreros and hitting pinatas. It was the result of capitalism in the 1980’s saw this as an opportunity to cash in on the cultural movement by selling alcohol and food at reduced rates.

We spoke with Evelyn BruMar, Executive Director and Founder of Casa BruMar, a local non-profit that is dedicated to working with LGBTQ+ youth, and is of native Mexican heritage. BruMar offered this statement, “Capitalism has reduced my culture into drinking games, gross misrepresentation of my people and insane profits for corporate America who perpetuates the racism we Mexicans experience.”

So how can this change? While we may never see restaurants like On the Border no longer promote it as just an excuse to get drunk, there can be a change in how it’s taught to children. and that’s through creating an anti-oppression curriculum. This starts by challenging children to think differently about what they’ve been taught up to this point about Mexico and its history. By removing the stereotypical approach, it opens the door for a greater understanding of those freedom fighters and those who lost their lives in the struggle for freedom. Honor heroes of the movement on both the national and local levels. Finally, if there are celebrations, include those who are actually from the culture, and events can take place in manner that addresses the history of racism and ways it can change.

By having a more inclusive teaching environment, the vision of equality can be shared with everyone, and that is something worth celebrating.

(The contents from this article first appeared in the Zinn Education Project’s article “Rethinking Cinco De Mayo.”