Restorative Justice: How Dr. Zachary Robbins derails Jim Crow discipline in schools

“By nurturing classroom communities where students feel an abundance of care, we create conditions that keep students present, participating, & engaged in teaching and learning.” – Dr. Zachary Scott Robbins

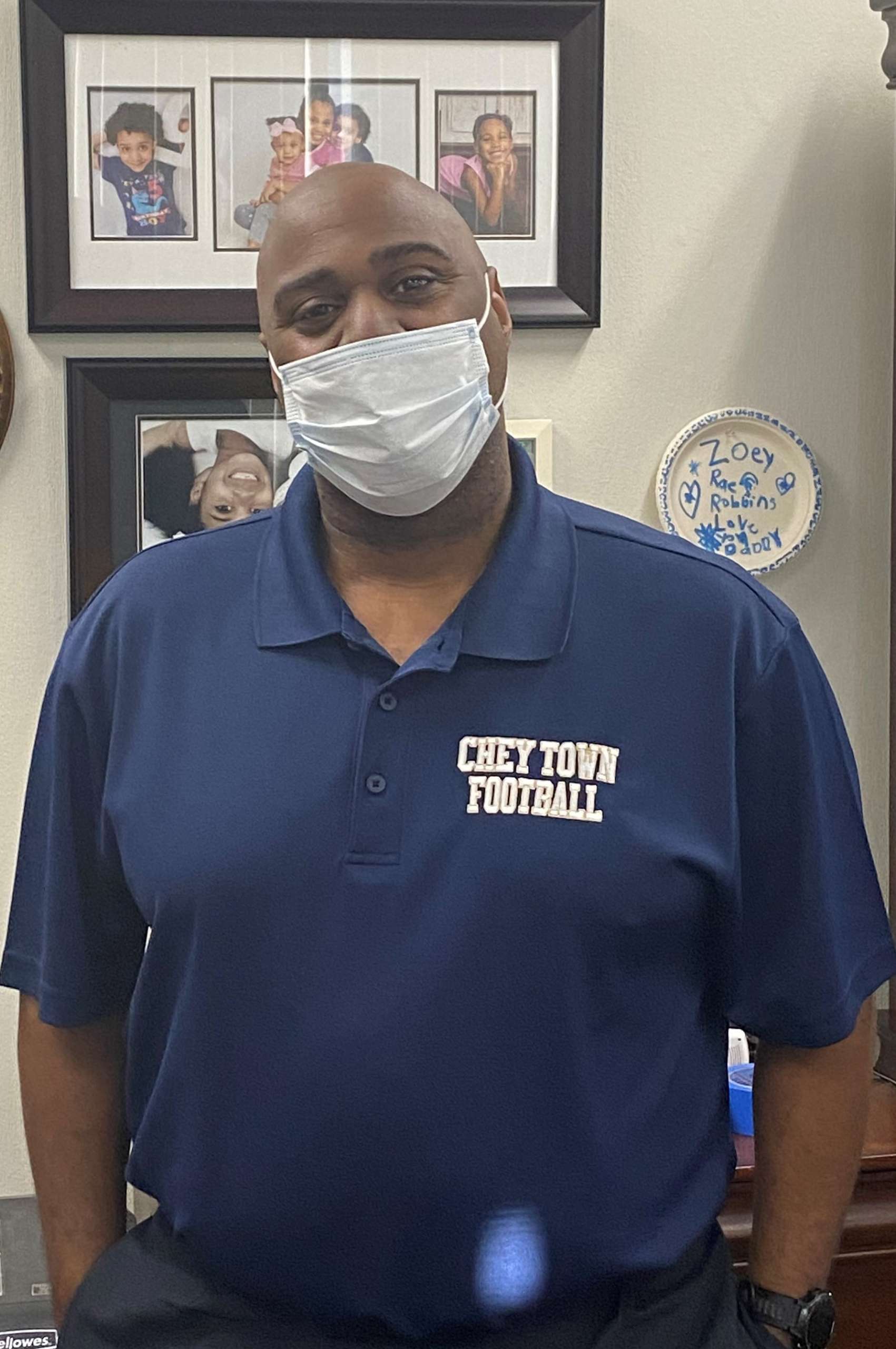

Dr. Robbins’ vision for education is more than just meeting academic standards; it’s about developing environments that fosters personal growth as well as skill acquisition for students. The former English teacher turned high school principal has been instrumental in the transformation of several secondary schools, from his days in Boston to his current position as principal of Cheyenne High School in North Las Vegas, Nevada. One of the greatest challenges he has faced is changing the way students, especially Black and Brown ones, are disciplined in schools. Upon his coming on board at Cheyenne, the Howard University and Boston College graduate saw a disproportionate number of minority students being suspended and/or expelled. After doing some intensive research and, as he calls it, “deep soul searching,” along with the input of students, created what is known as restorative justice tribunals in order to deal with the problem.

Recently we met with Dr. Robbins at his office to discuss what the conditions were like when he first came on board several years ago, how the restorative justice tribunals were instituted, and its success to this point.

He describes the situation upon his arrival after a successful stint as a principal in Boston. “When I first got here [the school] used to suspend and expel so many kids because it was the default way of classroom control,” he recalls. “We used to have so many referrals because that was the way for the teachers to maintain control; it was district wide.”

“So being one of three Black high school principals in Nevada who can give a comprehensive diploma, I couldn’t have it on my conscience that we were throwing so many black and brown kids out of schools. Something had to be done.”

“Looking on the outside, this looks like a middle class community, but most of the houses have been placed in Section 8 due to the financial/housing crisis [in 2008]. Almost 90% of our students qualify for free and reduced lunch but the way our surroundings look you would never see that. What many people don’t understand or know is that our schools is among one of the highest gang enclaves in Nevada, so we needed a new solution.”

“So what I did was that I took a team to a conference on restorative justice and about 80% of it was from the juvenile justice system. I said it wasn’t going to work. I did a lot of soul searching and came up with the restorative justice tribunals. Next, I had the students look into it, and they gave me some ideas. We came up with a prototype and just launched because we could no longer keep doing what we’re doing. We figured out that kids needed to be heard, and they had to develop skills so they would no longer repeat the same behaviors.”

“In that process we needed to give kids emotional, social and academic support. Also, we needed to mend relationships between teachers and students so when they return to the classroom there isn’t bad blood, where students feel that they are unfairly targeted and teachers know that a student isn’t out to sabotage learning. We had to get kids to take responsibility for their actions when they were wrong and get them to understand that they are part of a learning community.”

Robbins describes what took place after its initial launch. “We launched and the intervention worked, so we had students in the classrooms who were insubordinate, and through the tribune process we would find these mitigating things that would show why they acted up.”

“For instance, we had a child that got off work at 11pm and then wake up at 5am, then got to school late because they had to wake up their brothers and sisters. Upon getting to the school they may have had a situation with the campus security monitor who was just doing their job so by the time they get into the classroom they’re already upset. So when a teacher would make a reasonable request, the student would fly off the handle.”

“What we would discover is that the kids would not have the skills yet to process the moment. Or maybe there is a student in the class with a teacher who though the kid was doing something erroneously, but maybe the teacher didn’t know. In the tribunal, the kid will tell the truth. The counselor would give them the option that instead of an out of school consequence, the kid would prefer going to the tribunal. Next thing you know the student and the teacher would discuss what happened and there would be an understanding of why the action occurred.”

How did Robbins and the students get the tribunals going? “We wanted it to be therapeutic, something that could remediate academic skills is allow children to navigate different situations in the classrooms, as well as to heal relationships with teachers.”

Although the program launch was a success, he still had a challenge in getting the financial assistance due to a statewide budget windfall. “In terms of paying for it, we had to launch it in the middle of a budget crisis. But still, we had a crisis of disproportionate suspensions. In the first year, we were in a budget crisis. I asked for more money, and we got one position to bring on a counselor who could have a reduced caseload so I can teach them how to do this. We really needed seed money, and it was there. We got a great return on investment.”

Now that the program was able to run, what were some of the skills that students acquired?

“When kids go to the program, they don’t come back. That was amazing to me. When you have more than 900 cases over 5 years, and you have so few kids coming back and continually getting in trouble, It means something is working, and this is kids getting the skills.”

He brings up on example of how the tribunals are helping. “For instance, we will use a social emotional curriculum to teach certain things, such as teaching a labeling lesson. A kid will call another kid a name, or something that happened on social media, by labeling a kid something they are not. So we have a labeling lesson as a pathway to our restorative justice process.”

“We address the following questions: What is labeling? How do you actually do it, and how do you feel when someone labels you? We have something called the Reality Ride, it’s from the Capturing the Kids’ Hearts curriculum. When you have those ups and downs, there’s a way that you can process them. When you hit that challenge you know how to deal with it in a way that is constructive and not destructive in a positive way.”

“Those are the kinds of lessons we teach kids, so when they confront a certain set of variables start to become evident and clear, they have a set of skills that helps them to deal with it going forward.

In addition to the students acquiring skills, one of the most important is empathizing for their educators as well. “There is a power difference between teachers and students, and we have to let students understand that teachers are humans too. Understanding that when they’re not behind the desk teaching them the curriculum and leave this place, they also have the same stressors as your parents. Some have children to attend to, they have to figure out they’re going to pay for bills, and how they’re not going to disappoint you and make sure you’re happy in class. Teaching kids these social, emotional lessons they know how to navigate through them is important to create a learning environment in the classroom.”

Speaking of the teachers, how was he able to get their buy-in? “In the beginning, we didn’t get unanimous buy-in from teachers. From some, but not all. When we first began, we had two restorative justice facilitators. One of them said, “I don’t want to do this.” I said to them, trust the process. After she began to do it, she saw the utility, she saw the impact, she became a Rockstar. That is the person who was the facilitator. Ultimately, she moved on and is now in a PHD program. She went to work for the district and became a project facilitator for the whole district.”

Robbins continues on in in terms of staff buy in. “For some [staff members] their perspective was, “When kids act up they should be punished.” It’s not uncommon, there are states still with corporal punishment in their by-laws. As we continue to program, that was not the majority. There were some who said, “We have to do something different.”

“Over time, folks began to see because they saw their classrooms changing. It’s very powerful when you see a child who was just mean to them and then that same student comes back and reads an apology note to the whole class that is sincere. The student is no longer one who is so defiant; they’re trying a little harder. Before reading that note, they’ve met with the teacher and administrator who will be there in the tribunal, and the whole process is voluntary. The parents and student says I want to do this in lieu of being put out of school. For my students there are those who say I want to do this instead. Families are opting to say no, you are wrong, you need to repair the wrong you did.”

One thing that Robbins has implemented within the restorative justice tribunals is the understanding that there are levels to which it is applied. “I don’t want to assume that everyone is naturally wired to be a restorative justice facilitator. Everyone is not naturally a mentor or deeply empathetic. I don’t want to mandate it, so for the last five years the tribunal happens outside of the classroom. When there is an infraction, they will go to the administrator. That administrator will then say, we can make this into a tribunal if it’s a low level infraction.”

“For instance, if there is a fight, they will have the suspension and then come back and do the tribunal. The kids pushed for that to be added into the tribunal. The administrators will tell them to go to the tribunal. Now we’re at a point where the staff will do it and are learning the circle process.”

As successful as the tribunals are, Robbins emphasizes that the primary goal is to create an environment where learning is continuous. “I don’t want to stop instruction to run a circle, because learning never stops. Nothing eclipses the goal where we can get kids to be where they need to be academically. Now, we have 25 out of 110 staff who says they want to be trained. Even in that training I’m going to keep hammering that we’re not going to stop instruction. If you have an incident that impacts the entire class, that is when we’re going to run a circle.”

“We had a situation where a student was using homophobic slurs and it offended a lot of kids in class because they were very upset that this student was attack and the teacher thought that class couldn’t continue because the students were so upset. That’s when we stopped school because we had to heal the harm that was done.”

“The circles can be time consuming as it can take up to 40-45 minutes because they were upset that the student who committed the harm was so mean to their peer, but it touched them because they had family members who are homosexual. So, it touched them in a different way, and they said we don’t accept this. Having the circle was so needed.”

“Being able to apply a program such as the restorative justice tribunals also means having a level of cultural competency within the schools. The context of every school is different. With anything, how a school functions where we have almost 90% of the students living in poverty where they are students of color and are two or three grade levels behind in language and math.”

“You have to tailor your restorative practice response to the needs of the campus on what the data is telling you. If you look at the data and you see that primarily students of color are being suspended your cultural competence approach has to be tailored to that reality. You’ll find that why is it that there are no young ladies in your higher level math class, then that is a cultural competence issue. You can’t have a one size fits all approach, because how a lack of cultural competence manifests given the context of the school.”

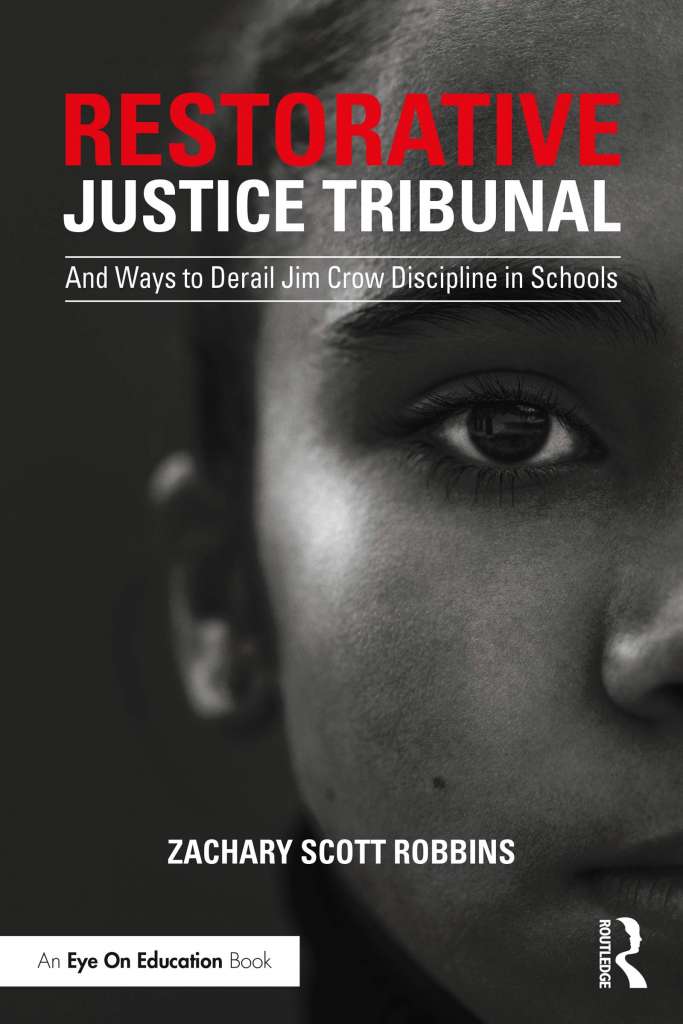

Next month, Robbins’ book will be released, so what is one thing he hopes readers will take away from it? “When people read the book, I want people to read it and take away that we can’t increase the achievement of schools by throwing kids out of them. We have to find ways to have all kids be successful academically by keeping them there and making sure they’re heard, loved and appreciated in enlisting their families as partners in the learning process.”

“So many things go wrong when we don’t listen to the needs of students. They will tell us what they need, we just have to listen.”

Dr. Robbins’ book will be available on May 10, and copies can be purchased on Amazon. He can be reached on Twitter as well.