Migrant children in Virginia: Where are they and are they getting an education?

by Nathaniel Cline, Virginia Mercury

Bryan Viera, who arrived in America unaccompanied, and Millie Okoro, who arrived with family, migrated from different countries to the U.S. as teenagers, both to make a better life for themselves and to make their mothers proud.

They enrolled in and graduated from public high schools in Virginia, leaning heavily on the support of a few counselors, teachers and groups that work with migrant youth to attain their educational goals. Now young adults, Viera and Okoro’s journeys reflect that of thousands of youth the American government has released from federal custody to sponsors in Virginia over the past decade.

Migrant children are supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), which is responsible for providing asylum seekers, including unaccompanied children, with equitable, high-quality services and resources.

As part of the agency’s duties, the office is responsible for supporting unaccompanied children until it can release them into safe settings with sponsors, who are commonly family members, until their immigration proceedings.

From October 2014 to April of this year, the agency reports 33,812 unaccompanied children have been released to a sponsor’s care in Virginia. Virginia ranked eighth with the most children released in other states.

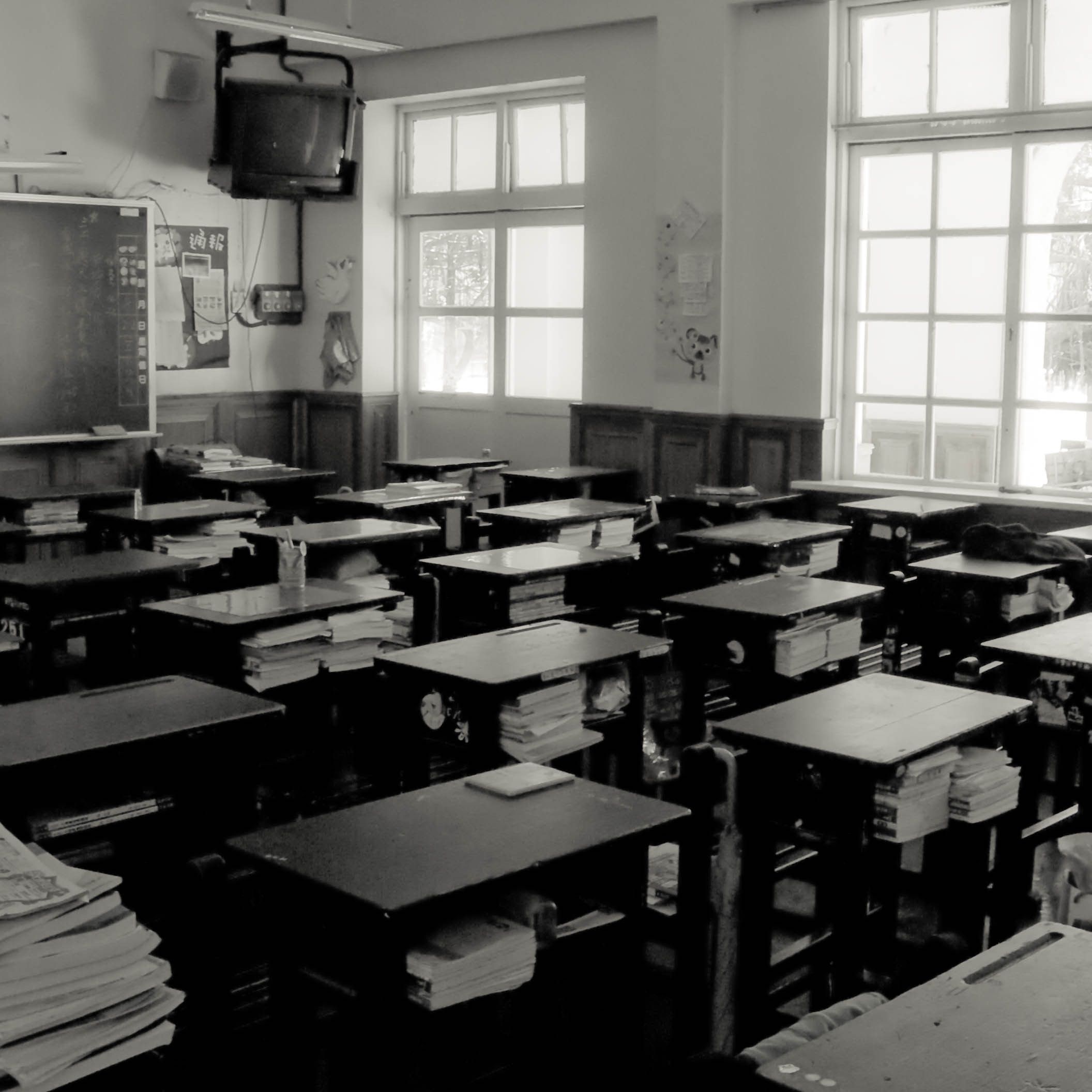

A federal law requires the commonwealth to provide all children, including migrants, “equal access” to a public education, regardless of their or their parents’ actual or perceived national origin, citizenship, or immigration status. This means migrant children may be navigating the same challenges Virginia-born children are facing, as the state grapples with declining assessment scores, striking policy issues and troubling student absences.

Leaders and media reports have also questioned the disappearances of migrant children in the U.S. and Virginia, youth who are from predominantly Spanish-speaking countries including Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. As of June 28, a total of 41 migrant youth have been reported missing from the Town of Culpeper, with Hispanic people representing the second largest portion of the residents.

What happens when migrant kids arrive in America, alone?

The ORR assists in finding a sponsor or family member to take care of children who arrive in America without their parents.

According to ORR, the office was created as part of the Refugee Act of 1980 to support refugees, unaccompanied refugee minors, and Cuban and Haitian entrants.

Since its establishment, Congress has expanded the office’s services to meet demands for asylum seekers, refugees, survivors of torture, unaccompanied minors, and victims of trafficking. The search for a sponsor can sometimes span the U.S.

Children who arrive to the U.S. without parents entered a sponsor’s care in 14 Virginia localities from Oct. 2023 to April 2024, including Loudoun, Arlington, Prince William and Fairfax Counties in Northern Virginia, the city of Roanoke in the Southwest region of the state, Norfolk in Hampton Roads, and central Virginia’s Chesterfield and Henrico Counties, as well as the capital city of Richmond.

Nationally, unaccompanied children were in the ORR’s care for an average of 27 days in 2023, which is the lowest annual average length of care per child since 2015.

A New York Times’ review of 2023 ORR data found 42% of unaccompanied children nationwide were released to a parent or guardian; in Virginia, 46% were.

ORR has organized with partners in Virginia to assist with resources including churches and social service groups. Virginia also provides services through the Department of Social Services.

According to ORR, the agency has no legal authority to compel children released or their sponsors to respond to inquiries or participate in such services that involve assistance with school enrollment or attendance and connecting the child or their sponsor to community-based resources suitable to their needs.

Virginia’s congressional lawmakers, including U.S. Rep. Morgan Griffith, R-Salem, have sought to improve operations around releasing unaccompanied minors.

In April, Griffith filed legislation requiring HHS to provide advanced notification to school districts and child welfare agencies when a minor is placed in their respective jurisdiction.

“Unaccompanied minors are crossing our southern border in record droves,” said Griffith, in an April statement. “ORR currently fails to notify any school district or child welfare agency if an unaccompanied minor is placed in a home, leading to issues of illegal child labor and abuse. The Unaccompanied Minor Placement Notification Act changes this HHS policy and it will give some protection to minors from exploitation.”

State policy seeks to address absenteeism, language barriers to learning

Virginia lawmakers and school divisions have attempted to both support children who speak English as a second language — some of whom migrated to the country on their own — and tackle chronic absenteeism.

Like other states, the commonwealth has been dealing with a troubling trend of chronic absenteeism, or students missing at least 18 days of instruction for any reason, including excused and unexcused absences.

Okoro, who attended high school virtually for almost two years, said she wished she could’ve gone in-person sooner, but her family was concerned regarding her immigration status. But in 2023, her last high school year, she decided to go in-person.

“Everything was happening so fast at the same time, and I wanted to get a lot of stuff [done], but I wasn’t really aware of my situation,” Okoro said.

She said she was oblivious to preparing for college until she arrived and met with her college counselor, the Dream Project — a group that empowers immigrant students who face barriers to their education through mentoring and offering scholarships — and even a member of custodial staff, who spoke her second language, Spanish.

Viera added that the language barrier made it extremely difficult for him and other Spanish speaking students to follow classes. Later in his high school career, Viera said he started to recognize some of the gaps schools had in helping and encouraging migrant youth, including training staff.

He said he believes the lack of support for students who don’t speak English could be one of the reasons students are deterred from staying in school.

“They just didn’t know what to do with me, they didn’t know how to help me and I could see some of them felt really bad about not being able to, but it’s part of the lack of training that the [schools] give to the staff at the schools,” Viera said.

One of the keys to their success to finishing high school in Virginia and enrolling in college was their attendance at Virginia’s public schools.

“I just knew that if I needed help, I feel like education would have been … the first place to look for and so I tried as much as I could to limit the amount of absences I had, and if I had any absences, it was for a good reason,” said Okoro.

Viera said he’s uncertain where he would be if he didn’t show up to class, stayed after school or accepted volunteer opportunities. He recently graduated from college and is working in the technology industry.

“I feel like if I didn’t attend school as often, if I missed class, I feel like I wouldn’t have achieved or accomplished the grades that I had … [or earned] the scholarships that I [received],” Viera said.

According to a survey by the Virginia Association of School Superintendents, Virginia’s chronic absenteeism rate was more than four times higher during the 2022-2023 school year than pre-pandemic. Approximately a quarter of the 85 school divisions surveyed had a chronic absenteeism rate of over 25%.

In response, Virginia education leaders launched a task force to address students’ disappearance from the classroom and incorporated Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s “ALL IN VA” plan to combat the learning loss during the pandemic through “high-intensity tutoring” and promoting school attendance.

Superintendent of Public Instruction Lisa Coons said transportation, food and housing challenges can be factors for children missing school. Children may also be deterred from school because they are behind their class in learning, and may need mental health support, problems Coons said the state is working to correct as they try to educate caretakers on the resources available to students and the importance of being in school.

“We want to make sure that our students are in school because we know that’s the best place for them,” Coons said. “We know they access their learning and their experiences and their relationships with their peers and the adults in the school community, but it also provides support for some of those barriers that are hurting or causing students to not be able to be engaged as successfully and well in their education.”

In the last session, the General Assembly agreed to appropriate $72.1 million over the next two years to expand and provide targeted support for English learner students.

“English Learner students are one of the fastest growing segments of the student population, and their needs also vary greatly depending on their prior education experiences and English acquisition,” said House Education Chairman Sam Rasoul, D-Roanoke, during a February House Appropriations Committee hearing.

Sen. Ghazala Hashmi, D-Richmond, and Del. Michelle Malando, D-Prince William, carried successful legislation revising the state code to require that state funding support ratios of instructional positions for English language learner students based on each student’s proficiency level.

The budget includes language that directs the Department of Education to enter into statewide contracts for mental health providers for public school students and attendance recovery services for “disengaged, chronically absent or struggling students.”

Language was also added to the budget requiring schools that receive state funding for the “After-the-Bell” breakfast program to report their chronic absenteeism rates.

In Northern Virginia, Edu-Futuro, an nonprofit organization focused on empowering immigrant and underserved youth and families through education and workforce development, has helped to address chronic absenteeism among Latino youth and English Learner students by forming an outreach team tasked with contacting hard-to-reach students and their families, and working to return chronically absent youth to the classroom.

During the team’s first year in the 2022-2023 school year, Edu-Futuro returned 62% of the 273 children referred to them to the classroom in Fairfax County.

“Through working directly with hundreds of families, our outreach team has found that students often don’t want to abandon their studies,” said the organization in a 2022-2023 annual report. “They need encouragement and concrete help to address the underlying challenges that led to their absenteeism, such as financial struggles, mental health issues, or family crises that require the support of government or nonprofit partners.”

Del. Alfonso Lopez, D-Arlington, proposed the state appropriate $400,000 over the next two years to help Edu-Futuro expand its services to help reduce chronic absenteeism at public schools in Northern Virginia. The provision was not included in the state budget.

Legislation carried by Sen. Todd Pillion, R-Washington, to address chronic absenteeism was continued to next year. The companion bill carried by Del. Israel O’Quinn, R-Washington, which was left in the House, would have added the definition of “educational neglect” into state law and required school staff to report to authorities if a parent’s child is not attending school regularly.

Karen Vallejos Corrales, executive director of the Dream Project, said she hopes lawmakers will continue to support and invest in counselors and parent liaisons to help migrant youth when they arrive.

She also hopes lawmakers will continue to support career and technical education programs for students, in-state tuition for students who are undocumented, and supporting state aid for students who go to public universities in Virginia.

“Increase resources and support to all students regardless of immigration status, so that all students who go through our public school system are able to benefit equally and contribute back to the communities they grew up in,” Corrales said.

Continuing challenges: Many migrant children disappear and others work dangerous jobs

About 85,000 migrant children have been reported missing, some of whom have later been found working dangerous jobs including in some hazardous environments. These same problems can be a cause for concern after children are released from ORR’s purview.

Culpeper Police Department Sgt. Norma McGuckin, who has leading efforts to find dozens of missing migrant children, said the area is known among the Hispanic community as a good place to find steady landscaping work.

McGuckin said one of the most surprising takeaways from her investigations is that out of the 41 children who have disappeared from Culpeper, only a handful of children are enrolled in school. Culpeper Police Department keeps an online record of missing children.

Sponsors McGuckin has worked with in prior investigations are frustrated when children disappear, yet afraid of reporting the children out of fear they will be returned to their home country. She added some of the older children also have a sense of responsibility to support their families back home financially, so they’re more focused on finding work than studying schoolbooks.

“They do want to do the right thing and they do want to help these children to succeed in this country the best way that they can provide them help with, but unfortunately … the child already has this plan in mind when they come in across the border that they came here for work,” McGuckin said.

Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares has called the situation “a serious emergency that is being ignored by the federal government.”

“Vulnerable unaccompanied minors are being dropped off in our cities and counties, and local social services and law enforcement agencies have no idea,” Miyares said in a February statement after writing a letter to the White House about the problem. “How can they protect and check in on children they don’t know are there? We must advance federal, state, and local collaboration in the face of this unprecedented, horrifying crisis. No child should experience the uncertainty and vulnerability that these children are facing.”

Also in February, the Office of the Inspector General published a report that found gaps in ORR’s screening and follow-up process with sponsors. The office reviewed the ORR’s processes, including its post-release services, following a surge in referrals of unaccompanied children in 2021. Once the office examined data from March to April of that year, the Inspector General recommended changes to how ORR screens candidates for sponsorship and monitors them.

“It is important for ORR to protect children from unsafe placements by taking appropriate steps to screen sponsors while also releasing children from care in a timely manner and without unnecessary delay,” the letter states.

The office found that in 16% of children’s case files, one or more required sponsor safety checks lacked any documentation indicating that the checks were conducted. The office also found that the case files of 19% of children released to sponsors with pending FBI fingerprint or state child abuse and neglect registry checks were never updated with the results.

Jeff Hild, acting assistant secretary of the Administration for Children and Families in the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the program ORR, said that the period reviewed was one of the most “challenging periods in ORR’s history” amid a historic number of unaccompanied children placed in ORR care, the largest and fastest expansion of emergency capacity, and at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“As ORR worked quickly to respond to this unprecedented emergency, and with limited resources, it prioritized the safety and well-being of children at every step,” Hild wrote in December before the report was published.

Hild said in a nine-page response that the office is working to meet the recommendations.

Efforts by the Center for Public Integrity and Scripps News helped lead to a policy change with ORR after investigators were denied information to find missing children.

In February 2023, ORR entered into an agreement with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to provide all available data that might help locate the child.

Then in August, ORR updated its policies to clarify that, in cases of missing children, it will share information with investigative agencies without having to go through the full case file request process.

Some kids who come to Virginia from other countries find themselves working hazardous jobs that put their lives and health at risk.

Virginia recorded 302 child care labor violation cases from 2020 to 2023, according to a child labor report compiled by the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy, released in March of this year.

“Because most labor violations go unreported, the actual number of child labor violations are likely to be significantly higher than those reported,” the center noted.

More than half of the cases occurred in 2022.

Citing research that found teens who work more than 20 hours tend to have lower grades, more absences and higher dropouts, the center’s report underlined the importance of child labor laws. The report also said young workers have higher rates of job-related injuries and injuries that require emergency department attention.

The Department of Labor began a federal investigation into illegal child labor performed by migrant children following a damning report last year by the New York Times.

Last September, the agency confirmed that it was investigating Fayette Janitorial Service, LLC, a company that had provided contract cleaning and sanitation services to slaughterhouses and meatpacking companies nationwide, including Perdue Farms, where the agency alleged migrant children were being used to clean slaughterhouses at Perdue’s plant on the commonwealth’s Eastern Shore.

“High-profile cases occurring in Virginia that are being investigated at the federal level have detailed children cleaning equipment with acid and pressure hoses,” the Interfaith Center’s report stated.

The Times found that Marcos Cux, who migrated to Virginia from Guatemala, was hired at age 13 to work an overnight shift at an Accomack County Perdue plant, one of 15 migrant youths working there. None were older than 17. Cux’s forearm was torn “open to the bone” by a conveyor belt in the poultry deboning section of the plant he’d been sanitizing, the Times reported. He was in eighth grade at the time.

(Virginia Mercury is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Samantha Willis for questions: info@virginiamercury.com. Follow Virginia Mercury on Facebook and X.)