McClellan, Spanberger work to repeal parts of 19th century law that could ban abortion nationally

by Charlotte Rene Woods, Virginia Mercury

Democrats are finally talking about the Comstock Act — and they are finally trying to repeal it.

The act is a dormant 19th century federal law that’s still technically on the books and could be used to implement a national abortion ban. Named for activist Anthony Comstock who pushed for it, the 1873 law prohibits the mailing of “every article or thing designed, adapted, or intended for producing abortion, or for any indecent or immoral use.”

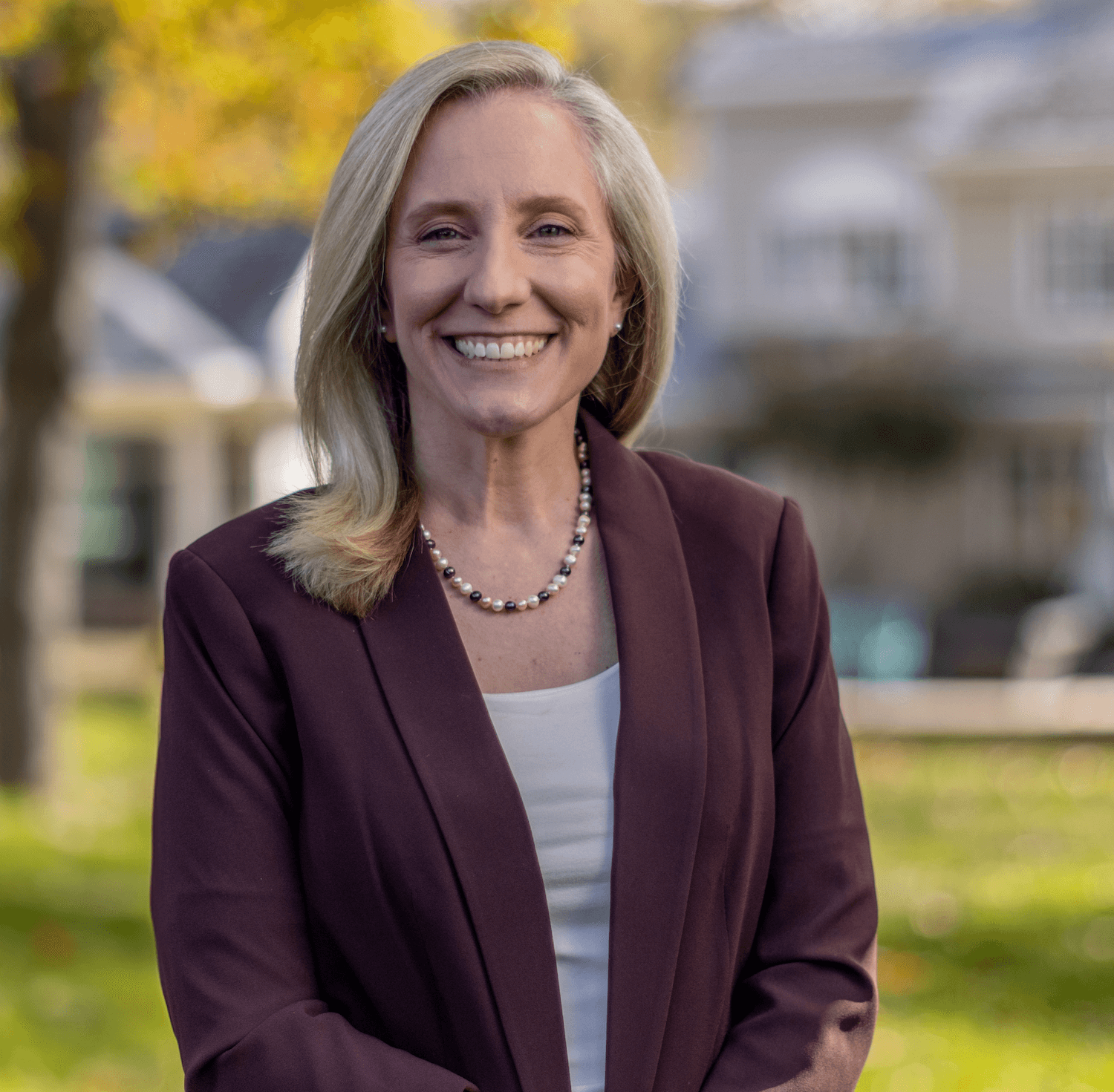

Dubbed the “Stop Comstock Act,” U.S. Sen. Tina Smith, D-Minn., announced legislation last week that would repeal portions of it. A House version of the bill is co-sponsored by Virginia Reps. Jennifer McClellan, D-Richmond and Abigail Spanberger, D-Henrico.

More broadly, the Gilded Age-era law focuses on obscene materials such as pornography, but other provisions of it have included abortifacients and contraception. The contraception components were stripped away over the years. While its abortion components have not been enforced, the law has been used in child pornography prosecutions.

Four previous attempts from decades ago to repeal the abortion components of the act have failed and McClellan was candid about how her bill may not see success in the U.S. House right away due to its current GOP control.

“That doesn’t mean we don’t start fighting,” McClellan said, noting how it took her about a decade to pass legislation to remove abortion barriers when she was a state senator in Virginia. “Hopefully it will be the next Congress, under Speaker Hakeem Jeffries, that we pass that bill.”

Jeffries, the House Minority leader from New York, stands to become the next Speaker of the House if Democrats are able to take control of the chamber in this year’s elections.

Showing their work on Comstock can help Democrats communicate about threats to abortion access amid this year’s presidential and congressional elections, said Erin Covey, an analyst for the Cook Political Report.

“I think the reason that this is coming up now is because we’re getting closer to the presidential election,” she said. “The potential reality of a second Trump term is something that Democrats in Congress are reckoning with right now.”

Why does this particular law matter?

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump has taken credit for how his Supreme Court picks during his presidency ushered in the fall of Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court ruling that federally protected abortion for nearly 50 years. With speculation at how far he would seek to regulate abortion, he’s said different things in interviews with national press over the past year.

While President Joe Biden has made abortion protection a pillar of his re-election campaign, Trump has made various statements ranging from supporting a national 15 or 16 week ban, to leaving regulation to the states, and “feeling “strongly” about Comstock.

In an April interview with TIME Magazine, he said he’d have a “big statement” within two weeks, but he never did.

He also said earlier this month that he would “work side by side” with a group that wants to see abortion “eradicated.”

And though Comstock’s abortion provisions were not enforced during the nearly 50 years of Roe, it has been a looming specter for the abortion rights movement all along. Activists and legal scholars have cautioned about its potential as it is still technically on the books.

It was a Trump-appointed Texas’ judge’s interpretation of Comstock that helped propel the Federal Drug Administration v Alliance For Hippocratic Medicine to the U.S. Supreme Court. Though the Supreme Court, which has several Trump appointees, did not rule in the Alliance’s favor, they kicked the case back down to lower courts where it will continue to be litigated.

Most directly, the Comstock Act applies to mailing abortion medication, but some think it can be interpreted further to prohibit transport of supplies to establish abortion clinics.

While “not literally a ban,” legal historian Mary Ziegler explained how abortion opponents can interpret it to be used as one.

“The question is, if you can’t put anything in the mail or through a common carrier or potentially into interstate commerce, then how do you get surgical tools or whatever? How do you get any of the items you would need?” she said.

Comstock’s legal code appears in a conservative manifesto called “Project 2025” that Trump could tap into should he win a second term.

Chapter 14 of the policy guidebook by conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation recommends that promotion and approval of mail-order abortion medications cease and alleges they are “in violation of long-standing federal laws that prohibit the mailing and interstate carriage of abortion drugs.” Comstock’s legal code is then cited in footnote number 16.

Local government officials have tried for years to use Comstock to limit abortions in their communities.

The law has surfaced in local ordinances around the country, such as in Virginia where it was voted down last year and in New Mexico where legal challenges have ascended to the state’s supreme court.

Assisted by former Texas Solicitor General Jonathan Mitchell, Texas activist Mark Lee Dickson has encouraged localities to pass such ordinances. Dickson also has said that they offer legal representation to localities that “goes up” to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Be it Trump utilizing Comstock if elected, or legal challenges progressing successfully in Dickson’s favor through courts, Dickson’s confident it can be a path for a national ban.

“If enforced, it would have the same impact as a national ban on abortion,” he said. “That is because it is a de-facto national abortion ban.”

Legal historian Lauren MacIver Thompson, who specializes in Comstock, echoed Ziegler’s theory of how that could work.

“If Trump is reelected, (abortion opponents) basically have a clear path to enforce it with a newly re-formed Department of Justice,” said legal historian Lauren MacIver Thompson. “They can kind of read the act however they want it to be read.”

(Virginia Mercury is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Samantha Willis for questions: info@virginiamercury.com. Follow Virginia Mercury on Facebook and X.)