Henrietta Lacks’ family finally got their due; many more never will

by Samantha Willis, Virginia Mercury

The descendants of Virginia-born miracle woman Henrietta Lacks finally won a major settlement with a biotechnology company that profited billions from Lacks’ ever-reproducing cells; I congratulate them. The hard-won settlement is a glimmer of justice flashing within a dark facet of America’s medical and scientific progress, fields fueled by racist, unethical practices in the past and present that have taken so much from Black people and given very little in return.

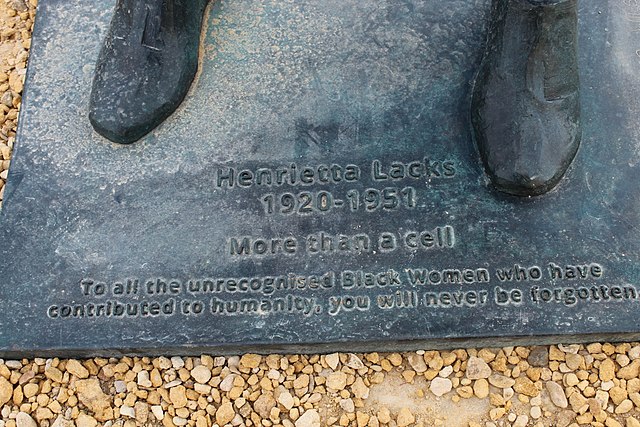

Lacks, born in the rolling hills of Roanoke and raised in Halifax County tobacco country, changed the course of medical and scientific history without ever knowing it.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University Hospital harvested cells from Lacks’ body without asking her or telling her they were doing so while she was being treated for cervical cancer there in 1951. They did so because they discovered Lacks’ cells lived on and on, never dying and instead, astonishingly, reproducing.

The cells, which scientists dubbed HeLa after Lacks, became a foundational force in research into diseases like polio, cancer and COVID-19. Lacks’ cells were the first human cells sent into space, the first human cells to be successfully cloned. Scientists used them to study the effect of radiation on humans. It is no understatement to say that many of the medical breakthroughs of the 20th century, progress that increased the quality of life for untold millions of Americans and others worldwide, would not have been possible without Lacks’ cells.

They also became an engine for others’ profit. Companies worldwide have for decades been reproducing and marketing HeLa cells, raking in billions.

Yet Lacks herself never saw any benefit from the use of her cells in her lifetime, nor did her family, which struggled with chronic illnesses and financial insecurity after her October 1951 death. Where is the fairness in that? The settlement the family reached with the biotech company Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., whatever the amount of money, is not enough to compensate for the incalculable benefit to humanity that Lacks’ cells provided, but I’m glad they got something.

What about the other Black Virginians and Americans who have also contributed to medical and scientific progress? What is their reward and legacy?

The sepia-skinned victims of Richmond grave robbers – the unidentified Black people whose bodies were stolen and dissected so that physicians at Virginia medical schools could better study anatomy – what payment did they or their relatives get for giving their bodies into the hands of white medical professionals? None.

What about the thousands of African Americans who were forcibly sterilized, sometimes without their knowledge, under the state’s 1924 Eugenical Sterilization Act — legislation that wasn’t outlawed until 1979? For the destruction of their reproductive abilities, sterilized Virginians may now, after applying for a program and enduring screening by an advisory panel, be eligible for $25,000 compensation, itself “contingent on the availability of funding,” through a state compensation fund created in 2017. That little bit of money doesn’t come close to balancing the unknowable loss of these peoples’ potential progeny, but it’s apparently the best Virginia can do.

What about the 600 Black men infected with syphilis as administrators of the Tuskegee Experiment – including three University of Virginia alumni who served as surgeon general and assistant surgeon generals of the U.S. Public Health Service – watched the disease ravage them, never offering penicillin to treat the condition? What benefit did they reap? Many of them had died by the time a class-action lawsuit awarded a piddly $10 million to survivors and their descendants in 1974.

Will the nameless enslaved women subjected to the between-the-legs butchery of J. Marion Sims, the so-called “father of gynecology,” ever get their due, or will their families be rewarded for their foremothers’ sacrifices? Probably not.

Indeed, today’s Black Virginians are largely descended from enslaved laborers, builders, cooks, craftsmen, businesspeople and thinkers whose unpaid efforts laid the foundation for this state and this nation. Reparations, though, the idea of paying Black people for centuries of their ancestors’ free labor, work upon which most American industries were built, is still a bad word in many circles. Even among people more open to the possibility, the “how” outweighs the “why,” and year after year, we do nothing to make right so much that was and is wrong.

We can and should celebrate the victory of Lacks’ family’s settlement, but we must understand that she is but one Black person whose contributions counted for a lot while they themselves benefited maybe just a little – or not at all. With Lacks in mind, we must endeavor to correct the harms of the past – yes, sometimes with cash – in order to forge a more equitable future for all of us.

(Virginia Mercury is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Sarah Vogelsong for questions: info@virginiamercury.com. Follow Virginia Mercury on Facebook and Twitter.)