Editorial: It’s Time to Kill the White Savior

It’s the holiday season, and across the country, people are preparing to get into the festive spirit. As people begin their celebrations, many will turn to their feel-good classic movies. But it’s time that we reflect on some of those classics and ask ourselves who feels good about them.

I distinctly remember the first time I saw “The Blind Side.” Based on a true story, the movie follows the life of Michael Oher, a former NFL player, who was adopted out of poverty by a white family. I was never a fan of sports movies, but this one especially bothered me.

Released in 2009, “The Blind Side” is what many would call a white savior movie, a story where a white character–in this case Sandra Bullock as Leigh Anne Tuohy–lifts a helpless Black character out of unfortunate circumstances, and, in the end, receives all the credit and praise for what that Black character accomplishes.

But “The Blind Side” is not the only example. There are plenty more–”The Green Book,” “The Help,” and “Freedom Writers” just to name a few. Some would even argue that “Dune,” 2021, falls into the white savior category, which is ironic given that the novel it is based on was originally written as a critique of the narrative. These stories all have one thing in common: a white character coming to the rescue to save poor, helpless people of color who are too weak to fend for themselves. I could write a beautiful intricate explanation about why it’s problematic, but I’ll say it simply. It is racist.

The story told in the 2016 historical drama “Hidden Figures” is one that needs to be told. The film focuses on the real-life story of Katherine Johnson, a Black mathematician who worked for NASA for more than three decades and played a key role in the success of countless missions. Without Johnson’s contributions, the United States would not have made it to the moon in 1969.

Unfortunately, “Hidden Figures” fails to deliver her story. One of the most iconic scenes in the movie is when Kevin Costner’s character knocks down a “coloreds only” sign from above a restroom. It’s a scene the director has defended. But it never happened. Al Harrison, the character played by Costner, never existed; he was a character created by the filmmakers solely for the purpose of having a white savior. During her time at NASA, Johnson defiantly used the whites-only restroom, but she did not receive support from her coworkers or superiors. Rewriting history to pretend that she did is offensive. Johnson is a hero. She became a hero on her own, not because of something a white man did. Adding a white savior to her story subtracts from everything she accomplished. Not only did she help the United States make it to the moon, she also fought segregation while doing it.

But white savior stories are nothing new, and they aren’t just in movies. They existed for more than a century in film, television, and literature.

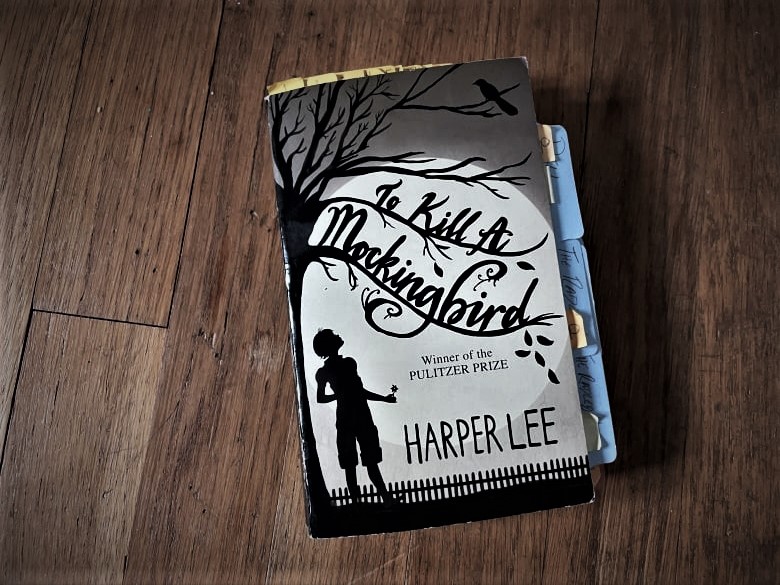

In 2018, a PBS survey. found that “To Kill A Mockingbird” by Harper Lee was the most loved book in America. “To Kill A Mockingbird” is potentially the most horrific example of a white savior narrative, and it’s shoved in the face of almost every high school student in the nation. The Black characters in the book barely have a presence–in fact, calling them characters is a stretch. They are props. They were created by the author to make a point about her story, not play a role in it.

When I was a freshman in high school, my pre-AP English teacher assigned us books that explored different cultures. We read books by Asian authors, Middle Eastern authors, and Latin American authors, but when it came to exploring the plights of Black Americans, we were assigned “To Kill A Mockingbird”, a white savior story written by a white woman.

When stories like “To Kill A Mockingbird” are taught in our schools and when movies like “The Green Book” win awards, it sends a message that white people are the only path to salvation for Black people. After centuries of slavery, segregation, systematic killings, and mass incarceration, I find it hard to believe any white savior narrative. It’s offensive to my family’s experience fighting racism to pretend that Atticus Finch is some sort of hero. The only thing someone can learn from “To Kill A Mockingbird” is how not to tell a story about racism.

At their core, white savior stories are stories about racism that focus on making white people feel good. But that itself is racist. Why should we prioritize white feelings when systemic racism is literally killing people? In 2020 alone, police killed almost 250 Black people. We cannot have an honest conversation about race if we value how white people feel over Black people’s lives.

Not only do these white savior stories uphold the principles of white supremacy, but they also send an aggressively vivid message to Black children: you will never be the hero on your own.

Movies don’t need to tell Black children that. They hear it enough from teachers, politicians, and the news. I know I did. With the way Hollywood characterizes Black people, it’s shocking that they haven’t tried to make the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. white.

We cannot fight racism when stories like “To Kill A Mockingbird” are so ingrained in our nation’s culture. If we are going to put an end to the idea that Black people cannot help ourselves without a white savior, then it is time to throw out “To Kill A Mockingbird.” It is time to bury it along with “The Blind Side,” “The Green Book,” and yes, even “Hidden Figures.” We cannot move forward together–we cannot fight racism–as long as we let white people pretend to be the heroes.

It’s time to kill the white savior.