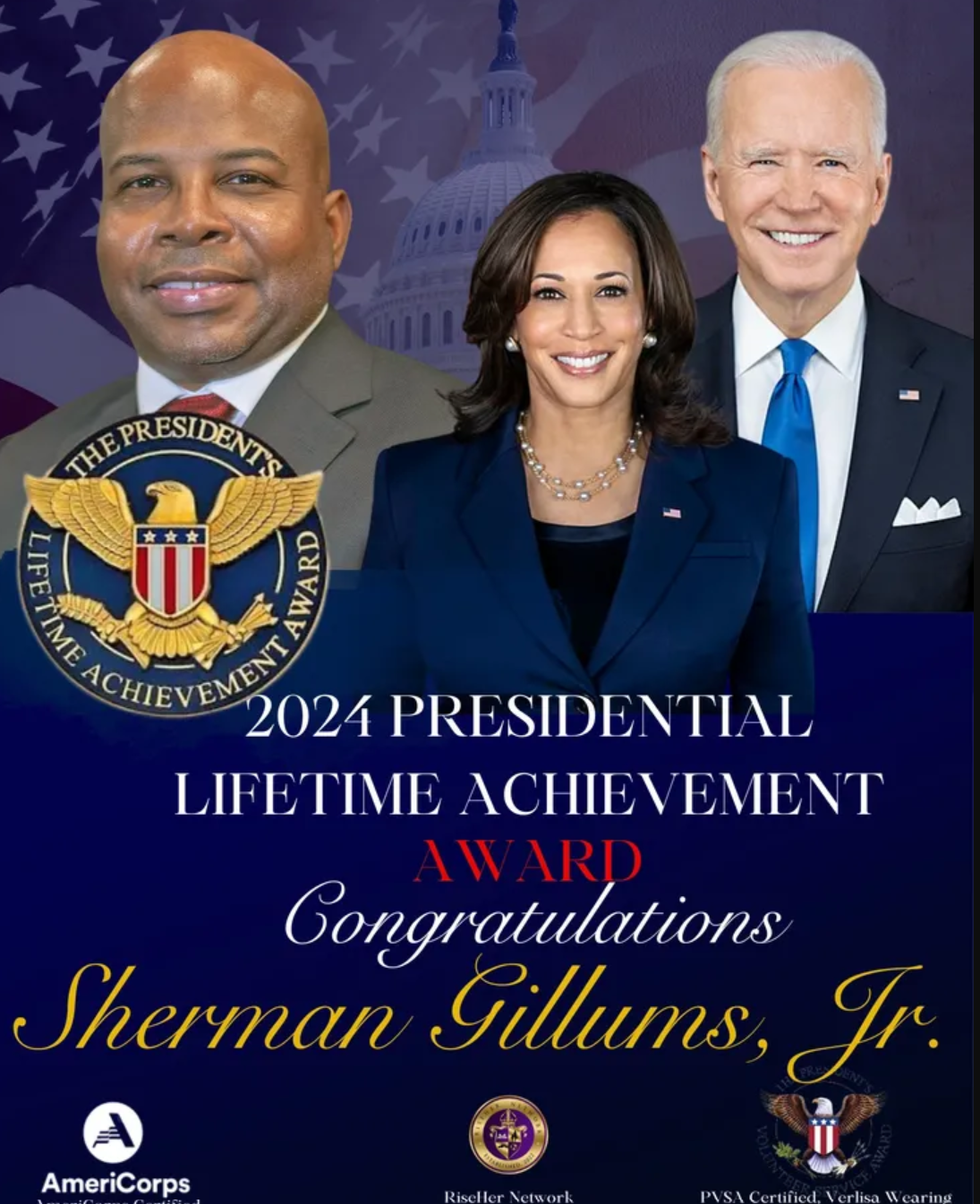

Dr. Sherman Gillums, Jr. speaks on being a Presidential Lifetime Achievement Award honoree

by John Reid

As the 2024 Presidential Lifetime Achievement Awards ceremony takes place on September 7, the PW Perspective spoke with Dr. Sherman Gillums, Jr. about the honor. According to his LinkedIn bio, Dr. Gillums served 12 years in the United States Marine Corps, enlisting at age 17 and receiving a commission as a “Mustang” officer before being honorably discharged because of an injury in 2002. After retiring from the military, he began a career in sociopolitical advocacy that spanned 20 years.

Gillums, who has also been a frequent contributor to the PW Perspective, talked about what it meant to be selected.

“To be honest, I didn’t even picture this happening,” he said. “You’re just doing the work and you don’t rack up the hours in your mind. It felt good to receive this honor, not just because it validated me, but validated the number of people who have been coaches and mentors in my life who would be proud of me.”

He mentioned how being a voice for veterans has provided a space to meet with policymakers. “The benefit is that it’s apolitical,” he said. “Sometimes, issues will be politicized, but not too many people want to be messed with politically. When you’re in the room with people in seats of power, and you understand how they relate to these issues, it gives you this inside scoop on how things get done. I could have different conversations, whether they were ordinary citizens, or leaders. Veteran suicide was a big issue, and it was apolitical, so I could do a lot of downloading, and it enabled me to understand the issues and become a bigger advocate in the public eye.”

Has the government given enough resources to veterans to help with mental health? “It’s the right questions, but the answer really depends on who you ask. The people who provide the funding in Congress will say yes they’ve done their part. We’ve given the agencies all they need. The people who run the program will say they’ve taken care of at least a hundred veterans this month.”

“When you ask the veterans who need the most help though, and they have conditions which may require special types of assistance beyond what is provided, it’s a different story. For some people, that can’t be the end of it, because we then turn inward to systems and look at whether it was the wrong type of medication, or therapy, or the more experiential aspects that don’t show up in data. I’ve had to really dig into what veteran suicide truly entails. A lot of it happened because too many doors were slammed in their face and they fell off everyone’s radar, and they were left with the one choice they felt gave them the ultimate control.”

One challenge is programs not having the correct information to help veterans, and Gillums says it takes more than elected officials to give them the help they need. “I don’t think you can rely on federal, state, or county government without community-based support,” he said. “While they do a great job of helping, it comes down to the type of veteran. They take on several identities, especially the home identity, and if you come home to an empty house, and you have an addiction problem, they’re going to put on a mask. Then we’re shocked when someone takes their own life.”

“Let’s take a look at their home life,” he continued, “see if there was a split in a marriage, or kids were estranged. A lot of things can have a person go over the edge, but it’s also combined with combat experience. The stress of being in the military for years, maybe being discharged, there are so many dimensions we have to look into, and one of the most important is society’s responsibility to the veteran.”

Besides being a voice for veterans, he has also worked on the caregiver support program. “The first federal advisory committee was established in 2017,” he said. “I joined with Elizabeth Dole on the inaugural committee. We talked with the caregivers, and then to the policies. This is where my expertise in veteran benefits helped, because once I could understand their experiences, I could match that with the policies available.”

The focus for him was ensuring caregivers received the financial support they deserved.

“There had to be someway we could compensate them fairly. Providing for the veterans’ families shouldn’t be a burden. We wanted to make sure caregivers had a voice, and their own standing identity to go to school, and give them the support.”

During his time as the disability coordinator with FEMA, he could use his experience to help disabled veterans, especially after the Hurricane Katrina tragedy in 2005. “Approximately 80% of the people who were abandoned and then died in Katrina were either disabled or older. That role focused on disability, and I was in advocacy for so long, being in that group helped me to be involved in two years ago. It helped me with a lived experience to have a fresh perspective on policy.”

However, as with many who experienced the pandemic, he dealt with the challenges of meeting fellow veterans in person and focused on his own health.

“After I pushed for the Mission Act for so long right before COVID, the pandemic happened. I became burned out because I couldn’t leave my house and interact with these veterans. I became an active suicide intervention, and you can’t do that over the phone or on Zoom. I took a respite for my own mental illness, and then I came out with this idea to do something bigger, and emergency responsiveness was the ideal solution.”

As he has become more focused on emergency responsiveness, it has helped him to bond even more with fellow Marines and continue his work.

“It is a culture which helps veterans hold on to their identity, and they gravitate to those roles. We celebrate the Marine Corps birthday every year, and it’s a reminder of the work we do.”