Confronting the “Name Blame Game” in Education

By Dr. Sherman Gillums Jr., University of Dayton

The results of my recently published research revealed that a person’s first name does more than individualize one’s identity or function as a primary interface with society. This lifelong label can also insinuate one’s ethnicity, family history, and community of origin to others. Reactions to what a parent names a child often reflect the impulses of a society with a history of assigning hierarchical values to identities, with higher values given to those most proximal to an oft unspoken yet mainstream, monocultural American identity. The difference in common reactions to a Brandon versus a Jamal can drive whether someone gets a job interview or access to credit markets, according to research. More often than not, studies on name-identity bias in K-12 education attributed the problem to the foreseeable consequences of giving a child a unique or unusual ethnic-sounding name.

Research has shown that a child with a name that seems “too black” is, on its face, likely to be associated with a persona that over indexes in negative social outcomes. This stigma will often carry into adulthood, where a higher likelihood of being passed over for a job or denied access to credit markets is statistically more likely to follow the name. A general impulse toward bias against Black-sounding names has also surfaced in Internet search algorithms and artificial intelligence applications. Interestingly, even a person who identifies as White with a Black-sounding name, as was the case with Jamaal Allen and Lakiesha Francis, who reportedly faced the risk of being the target of the same name-based hostility or discrimination that a similarly named Black person faced.

Nameism, a portmanteau of name and racism, did not appear in academic research prior to the publication of my research study and thus is coined herein as antagonistic attitudes and behaviors toward a person based on a presumed ethnic association signaled by a name. The antagonism can take on several forms, such as bias, prejudice, discrimination, or hostility. While negative attitudes toward names were also directed at other ethnicities, such as “Muslim sounding” names after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, “Asian sounding” names during the coronavirus pandemic, or “Mexican sounding” names in the illegal immigration debate, Black-sounding names are distinguished by the reason they came into form and their uniquely American origins in many cases.

Prior to the late 1960s followed by the “Black Power” and “Black is Beautiful” movements of the 1970s, Black families gave their children common names that demonstrated an assimilative intent. However, as the civil rights movement spawned the evolution of a diasporic Black identity based on shared experiences in America, naming conventions marked an increased preference for names that were unique and rhythmic, with the creative use of affixes and punctuation marks, that became associated with an assertive Black counterculture within a white-centered social structure. This counterculture drew reactions from White society that associated unique Black-sounding names with the stigmatized expression of Black culture and social norms.

Presumptions about the parents who gave their children such names imposed deficit views on the children themselves. Despite this, my study revealed that nameism had less to do with a parent’s shortsightedness regarding future reactions to a particular name. Rather, the problems began with the reasons a name aroused bias, prejudice, discrimination and even hostility in some cases. As racism has evolved in society, how it is expressed has as well within a racialized social order, where claiming to be “colorblind” reinforces the virtue of seeing the absence of one’s “color” as a positive. The reasoning starts with the fact that many parents give their children ethnically identifiable names, despite the future risks, precisely out of a desire to ensure a child’s identity is not simply absorbed into colorlessness.

This desire acts as a counterbalance to society’s demand for absolute identity assimilation, creating the intercultural tension that gives rise to nameism. Consequently, names viewed as distinctively Black give off a signaling effect that was empirically shown to be a barrier to a student’s chance at receiving a fair evaluation of academic potential. A lack of meaningful engagement with teachers was also correlated with names that announced a student’s minoritized identity in a culturally homogenous classroom setting. Whether as a student in a classroom or an adult in broader society, bearing a distinctively Black name was tantamount to limited potential based on the “tastes” of the whiteness-centered mainstream. While distinctively Black names have evolved over time and generations, so too had mainstream reactions to them.

Instances of socially acceptable nameism ranged from implicit to blatant, from names like Latanya being algorithmically associated with criminal records during web searches to a President of the United States who publicly maligned the name Ketanji (Brown Jackson), who happened to be the first Black woman to become an Associate U.S. Supreme Court Justice, during a campaign rally to the delight of attendees. These and other examples not only suggest a power dynamic at play whenever nameism occurred, but they also expose how the emergence of nameism within the norms and impulses of a White-centered monoculture gave anti-Black racial animus a new place to hide. The notion that structural forces enable nameism starts with the aforementioned pattern of sociocultural and interpersonal power dynamics that persist between Black and White people in society from the Civil Rights Movement to present day.

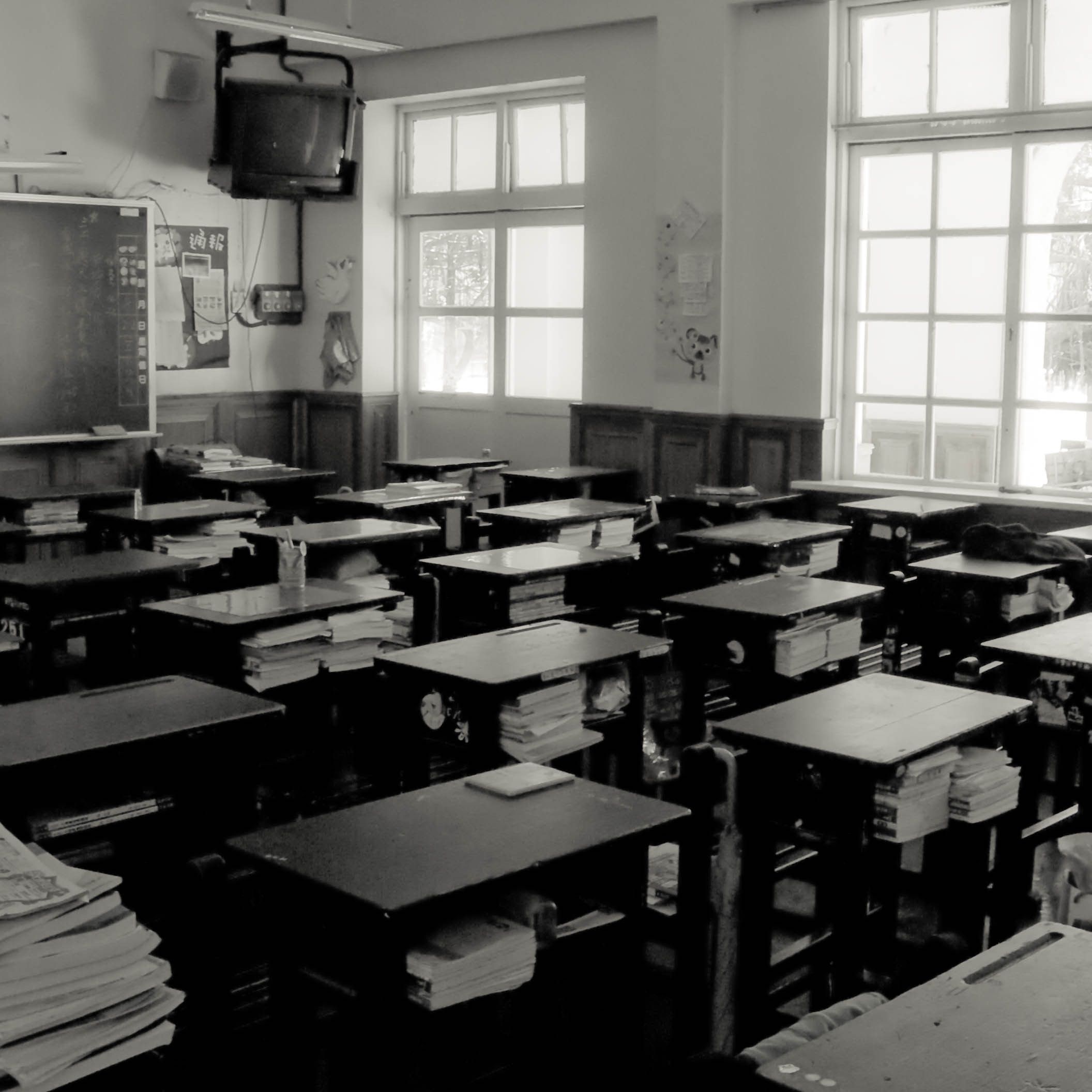

Relatedly, the U.S. education system is structured by rules on authority, subjective assessments, and standardized evaluations centered around an ideal social identity. This identity is favored and rewarded by power brokers in a society with a documented history of devaluing Black cultural symbols. Social networks in the classroom are formed around interactions that are colored by hierarchical assumptions on race, economic status, adjacency to power, and other factors that mediate connections between people, with names being the initial interface in many of these interactions. These structural forces generally go unnoticed in the everyday lives of students until a perceived identity-threat, such as constant name misspellings and mispronunciations by teachers, become norms. As revealed in my study, these perceived attitudes and behaviors on the part of teachers become objects within the consciousness of students.

Once the objects become attached to past experiences with racial hostility, a student need not know what a teacher intended to feel exposed to name-identity threat, which can impact self-esteem, sense of self-potential, and attitudes toward learning. I concluded that nameism created racialized hierarchies among learners by presuming the assimilative intent of one’s parents signaled by choice a name for a child — the one power Black families have held out of the reach of White society for decades. By confronting racialized hierarchies in the classroom through name-identity affirmation, peer perspective taking, and cross-group dialogues facilitated by teachers, classrooms can become models for rather than microcosms of society. Achieving this aim starts with a firm commitment to respecting a diversity of cultures in general and culturally informed name-identities in particular. Carrying it forward requires a shared, conscientious goal among school administrators and educators to operate as the “first responders” at the front lines of inequity in learning spaces.