Tell Us: Should Racism Be Declared a Public Health Crisis?

Recently Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak signed a proclamation declaring racism to be a public health crisis. Minorities make up more than half of the population within the Silver State. According to the governor, it is aimed at raising awareness “so Nevada does not perpetuate poor health outcomes due to systemic racism during and after the pandemic.”

The proclamation addresses unequal access to mental health services as well as minorities lacking educational and career opportunities. The goal is to create long term change across government, in addition to housing, educational systems, and change in the criminal justice system. He is working with the State’s Office of Minority Health and Equity.

According to the American Public Health Association, counties and cities in California, Connecticut, Georgia, Indiana, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Washington, Texas, Vermont, and Wisconsin have also declared racism a public health crisis with similar proclaimations for change.

Is Racism Really a National Health Crisis?

According to the American Public Health Association and many others, it is. Racism prevents people from obtaining their highest level of heath, it is the driving force of social determinants like housing and education, and it creates a barrier to health equity. APHA former president Camara Phyllish Jones, MD, MPH, PhD states that the existance of racism unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities and unfairly advantages others and therefore saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.

Racism is undeniably a health crisis issue. State and local governments are recognizing it and the countries leading medical organizations including the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics have released statements supporting this fact. “By definition, a public health issue is something that hurts and kills people ‘or impedes their ability to live a healthy, prosperous life,’ Georges Benjamin President of the American Public Health Association states.

In a statement by American Medical Association President Patrice A. Harris and Board Member Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, police violence is a reflection of the American legacy of racism — it’s a system that assigns, values, and structures opportunities while unfairly profitted some and disadvantaging others based on skin color.

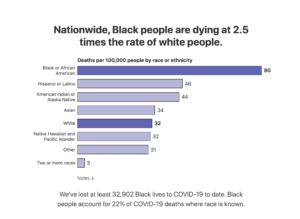

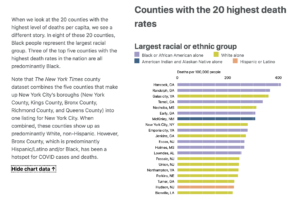

During todays COVID-19 pandemic, Black Americans are on average 2 times more likely to die from the virus than the general population. Dr. Abraar Karan from the Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston posted this on Twitter in June, “…disproportionately Black counties account for up to 60 percent of COVID-19 deaths in America, Black patients are less likely to receive a COVID-19 test if they need it, and that in most states in America COVID-19 disproportionately affects Black Americans compared to whites.” He believes that if legislators and health care professionals continue to examine racism as a public health crisis, policy can begin dismantling and restructuring problematic institutions. He stresses that communities need to start evaluating racism in their region’s particular context and how it impact all areas of life.

According to the COVID-19 Racial Data Tracker created in partnership with The COVID Tracking Project and Boston University’s Center for Anti-Racist Research, the virus affects Black, Indiginous, Latinx, and other people of color the most.

Another reason racism is a public health issue is that it can affect health care professionals’ decision to practice in underserved communities. The Nation’s Health published a summary of an August 2019 study that explored racism in medical schools and how it influences graduating doctors to practice in high-need communities. The data from more than 3,700 students at 49 US medical schools were collected from 2010 to 2014. Researches then narrowed the scope to Black Americans. Their study found that “explicit racial attitudes and ‘medical authoritarianism’ were associated with losing or having no interest in caring for underserved or minority people…” There was also evidence to suggest that the medical education system may also dissuade students from seeking a career in what is perceived to be a lower social hierarchy.

Another reason racism is a public health issue is that it can affect health care professionals’ decision to practice in underserved communities. The Nation’s Health published a summary of an August 2019 study that explored racism in medical schools and how it influences graduating doctors to practice in high-need communities. The data from more than 3,700 students at 49 US medical schools were collected from 2010 to 2014. Researches then narrowed the scope to Black Americans. Their study found that “explicit racial attitudes and ‘medical authoritarianism’ were associated with losing or having no interest in caring for underserved or minority people…” There was also evidence to suggest that the medical education system may also dissuade students from seeking a career in what is perceived to be a lower social hierarchy.

Study co-author Liselotte Dyrbye, MD, MHPE, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota weighed in. She advocates for more diversity training, student and staff inclusivity, and interracial interactions between medical students, staff, and patients. She states that students must be made aware of minority health issues and be given the opportunity to engage with a diverse patient population. Without an increase interest to service the Black community and other minority communities, the access and quality of health care will not improve and unspoken racist practices will continue.

In June, the PEW Charitable Trusts exposed the blantent failures to serve and protect Black communities “Black women are up to four times more likely to die of pregnancy related complications than white women. Black men are more than twice as likely to be killed by police as white men. And the average life expectancy of African Americans is four years lower than the rest of the U.S. population.”

Black communities have disproportionately suffered from more health issues than white communities. African Americans are more likely than whites to suffer from chronic diseases or health problems like obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

Critics of many of the states’ claim that their delarations are not enough and don’t outline concrete plans to remove racist policies and craft new legislation. PEW counters these arguments by explaining that declarations are only a first step in acknowledging institutional flaws, reexamining legislation, and restructuring organizations through the lens of anti-racism and anti-discrimination.

The journey to eliminating racist practices and policies will be a marathon, not a sprint. Tackling racism as a public health issue requires specific steps to dismantle institutions, reanalyze policies and practices, and reflect on subconscious biases. Public health experts warn that reversing these deeply rooted policies and practices could take decades to complete, but its a fight that must happen in order to improve equity in all areas of life — education, health, employment, etc.

Racism requires a fundamental redistribution of power, wealth and resources. “When you’re discussing things like that, there will be strong opposition and resistance,” explains Dr. Kimberly Jacob Arriola, profession of behavior, social, and health education sciences in the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University.

Dr. Arriola says that “to improve access to health care, you need to address the social disparities, which means poverty, education, employment, neighborhoods, safety, violence – those are all part of this larger issue of health inequities…So you can’t just pick apart any of those components…” She is extremely hopeful that the active involvement by young people and the recent declarations by many states will jump start reform not just in health care, but all sectors of social inequality.

Associate professor of Emergency Medicine at George Washington University Dr. Leana Wen explains that the history of redlining (the segregation of neighborhoods by providing or rejecting resources and services like home loans, education, and health care based on race) prepetuates racist policies and unfairly denies services to Black and Brown communities.

Dr. Leana Wen explains that we have to look at the whole picture “…you’ve got all these different levels of racism as a public health issue. So then you get to systemic racism itself, underpinning the health disparities…You have to backtrack into talking about racism as a public health issue…”

In closing, eliminating racism, discriminatory practices, and rewriting policy won’t happen over night. It’ll be a marathon, not a sprint, but the steps are being made. We cannot simply give up because the task is difficult. Racism is inbedded in our medical community and in the ways we are failing the Black and Brown communities. With these declarations and vows, we can begin reshaping and redefining our institutions through the lens of anti-racism and with the intentions equality.