Celebrating the Women Who Tell Our Stories

By Liletta Harlem

The theme of this year’s Women’s History month is Celebrating Women Who Tell Our Stories. When we reflect on telling our stories, it’s noteworthy to consider the story of Women’s History Month itself.

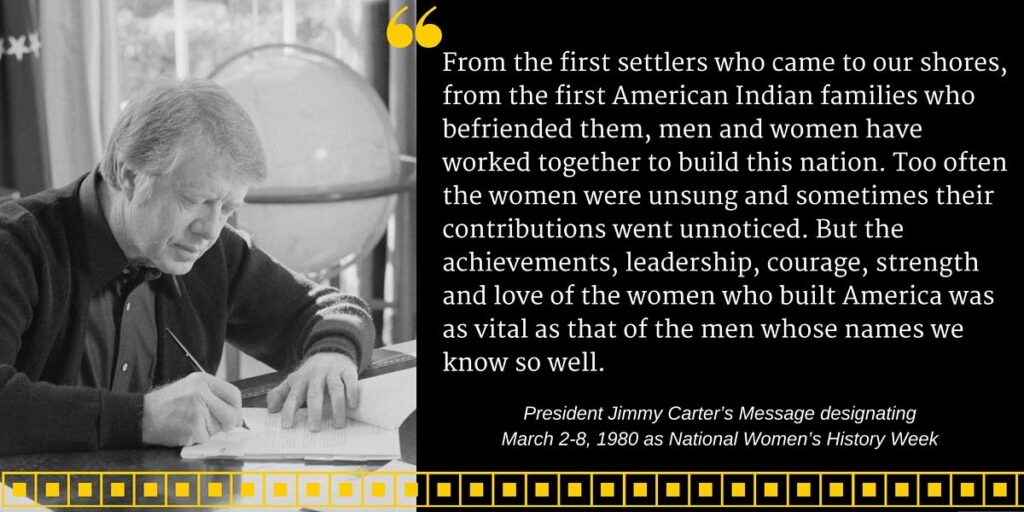

Originally, starting as a week only, in 1980, President Jimmy Carter made the first official proclamation to designate this week’s celebration as a national observance.

“From the first settlers who came to our shores, from the first American Indian families who befriended them, men and women have worked together to build this nation. Too often the women were unsung and sometimes their contributions went unnoticed. But the achievements, leadership, courage, strength and love of the women who built America was as vital as that of the men whose names we know so well. As Dr. Gerda Lerner has noted, “Women’s History is Women’s Right.”–It is an essential and indispensable heritage from which we can draw pride, comfort, courage, and long-range vision.”

I ask my fellow Americans to recognize this heritage with appropriate activities during National Women’s History Week, March 2-8, 1980.

I urge libraries, schools, and community organizations to focus their observances on the leaders who struggled for equality––Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Lucy

Stone, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Tubman, and Alice Paul.

Understanding the true history of our country will help us to comprehend the need for full equality under the law for all our people.”

Subsequent Presidents continued to proclaim a National Women’s History Week in March until 1987 when Congress passed Public Law 100-9, designating March as “Women’s History Month.” Between 1988 and 1994, Congress passed additional resolutions requesting and authorizing the President to proclaim March of each year as Women’s History Month. Since 1995, each president has issued an annual proclamation designating the month of March as “Women’s History Month.”

But now, let’s discuss our story! The very first line in the proclamation states, “From the first settlers who came to our shores, from the first American Indian families who befriended them, men and women have worked together to build this nation.” While that sounds notable, did this include Black women? Not really! Black women were not part of the first American Indian families, nor could we consider them part of the first settlers. In fact, the statement, “first American Indian families who befriended them” can give way to pause, as most American Indian families were violently forced to give up their homes, and made to assimilate to the European way of life, hardly worthy of being called, “befriending”.

Further discussion around the story of Black women. In areas where there was a small slave population, unlike the south, for example, was there a harmonious relationship between Black women working along with settlers to build the country? No. Unfortunately, our story was not so pretty. One article states regarding women slaves that lived in New England, ”Nonetheless, enslaved women in New England worked hard, often under poor living conditions and malnutrition. As a result of heavy work, poor housing conditions, and inadequate diet, the average black woman did not live past forty.”

It continues, “enslaved women were given to white women as gifts from their husbands, and as wedding and Christmas gifts. They had little mobility, freedom, and lacked access to education and any training. Female slaves were sometimes forced by their masters into sexual relationships with enslaved men for the purpose of forced breeding. It was also not uncommon for enslaved women to be raped and, in some cases, impregnated by their masters.”

This hardly sounds like the eloquent way that President Carter stated the history of women in America.

With that backdrop, however, many women, of all ethnicities, even under these grim conditions, did much to change to the conditions for women. Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Tubman, and Alice Paul, are among a few of the women in history that worked together to change conditions for women. But there were other women that seldom get recognized for their contribution to changing the conditions for women.

Isabel de Olvera, born in Querétaro, Mexico, in the late 1500s to an African father and an Indian mother. As a young, unmarried, free mixed-race woman in 1600, she sought permission and protection from the mayor of Querétaro to join an upcoming expedition to New Spain (or present-day New Mexico, Arizona and Florida). Isabel de Olvera’s existence as a free woman in the 1600s challenges the narrative that the Black experience in America began only when Africans were forcibly brought to this country and enslaved. Her journey is also among the earliest recorded instances of Black people fighting for liberty in North America, an act of resistance that is repeated throughout history.

Monemia McKoy, mother of twins Millie and Christine, In 1851, Monemia — already the mother of 7 children — gave birth to conjoined twins Millie and Christine. Despite her circumstances, Monemia fought endlessly for her children. As toddlers, Millie and Christine were sold, stolen and sent to Europe to perform. “In a staggering act of Black motherhood, Monemia travelled there, along with the girls’ owner and a detective,” wrote Drs. Berry and Gross in their book. “The three bought tickets where the 6-year-old twins were scheduled to perform. When Monemia was reunited with her daughters in the front row, she fainted.” Following this reunion in the late 1850s, the court in Birmingham, England, granted full maternal rights to Monemia. “For a rare moment in 19th-century history, a Black mother was reunited with her daughters because she was their mother, rather than taken away from them through the yoke of slavery,” they wrote.

The voice of the Black woman has often been silenced, or distorted, in order to amplify the voices of others. But throughout history, there have always been women of color who fought to change the status quo. Women who fought for motherhood and family. Women who worked hard and sacrificed for the greater good, often to her own detriment. These women will always tell the story of the character, the strength and the essence of a Black woman.