Solomon Carter Fuller: A Black pioneer for dementia research

By Liletta Harlem

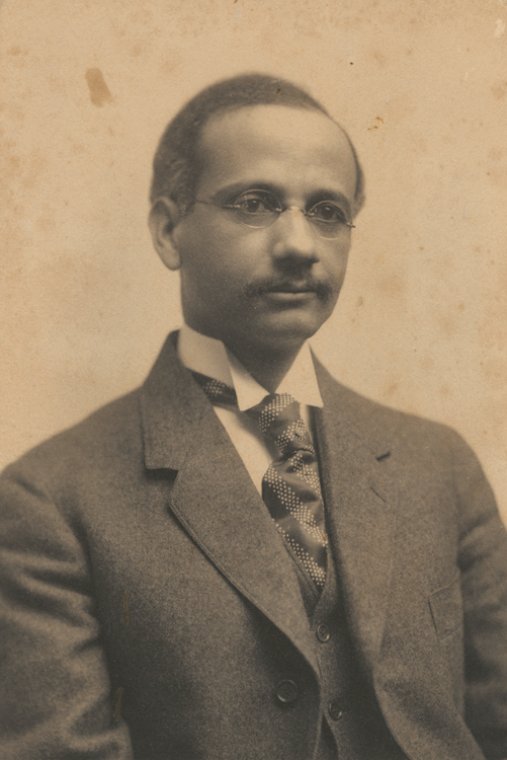

SOLOMON CARTER FULLER (1872-1953)

Did you know…

One of the first pioneers in dementia research was a Black man from Liberia?

Solomon Carter Fuller, an early 20th century psychiatrist, researcher, and medical educator, was born on August 11, 1872 in Monrovia, Liberia. His parents, Solomon C. and Anna Ursilla (James) Fuller, were Americo-Liberians. Solomon Carter Fuller was the first African American psychiatrist.

Solomon came from a family of innovators, as his grandparents were medical missionaries in Liberia.

In 1889, Solomon migrated to the United States to attend Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina. He then attended Long Island College Medical School and completed his medical degree at the Boston University School of Medicine in 1897. Fuller completed an internship at Westborough State Hospital in Boston and stayed on as a pathologist. He eventually became a faculty member of the Boston University School of Medicine.

Solomon’s Role in Alzheimer’s Disease

Solomon was one of five research assistants selected by Alois Alzheimer to work in his laboratory at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital in Munich, an experience that arguably paved the way for trailblazing research in Alzheimer’s disease. Dr Fuller was the first to translate much of Alzheimer’s pivotal work into English, including that of Auguste Deter, the first reported case of the disease. He published what is now recognized to be the first comprehensive review of Alzheimer’s disease, in it reporting the ninth case ever described.

Besides working with Alzheimer, Dr Fuller also worked to broaden his grasp of microbiology at the university’s Institute of Pathology with Professors Otto Bollinger and Hans Schmaus.

The secondment in Germany was short-lived but impactful; Fuller returned to Westborough Hospital in 1905, continued his role as neuropathologist, and founded and edited the “Westborough State Hospital Papers,” a journal that published local research activity. His interest in the eponymously named Alzheimer’s disease, coined by Kraepelin in 1910, led him to write extensively and become a leading authority on the subject.

In 1919, at age 47 years, Fuller resigned from Westborough Hospital and dedicated his time to medical education at Boston University. He became associate professor of neuropathology that year and, 2 years later, associate professor of neurology. Despite holding these positions and being the only African American on the faculty, Fuller found himself on the receiving end of racial discrimination. They paid him less than his fellow white professors and did not recognize him on the university’s payroll. From 1928 to 1933, he acted as chair of the Department of Neurology, but never received the title. In fact, his retirement in 1933, at age 61, came after they promoted a junior white assistant professor to full professorship and appointed the official departmental chair, a move Fuller felt may not have occurred had he been white. In his own words, Fuller commented, “With the sort of work that I have done, I might have gone farther and reached a higher plane had it not been for the colour of my skin.”

Upon his retirement, they gave Fuller the title of emeritus professor of neurology at Boston University, although he continued to practice neurology and psychiatry in Massachusetts and for a period in Pennsylvania.

Solomon Carter Fuller was a father and husband, a keen gardener, and master bookbinder. For the scientific community, he was an outstanding physician. His career trajectory may have been greater had he not been African American, yet this did not hold him back from becoming a pioneer in Alzheimer’s disease research.

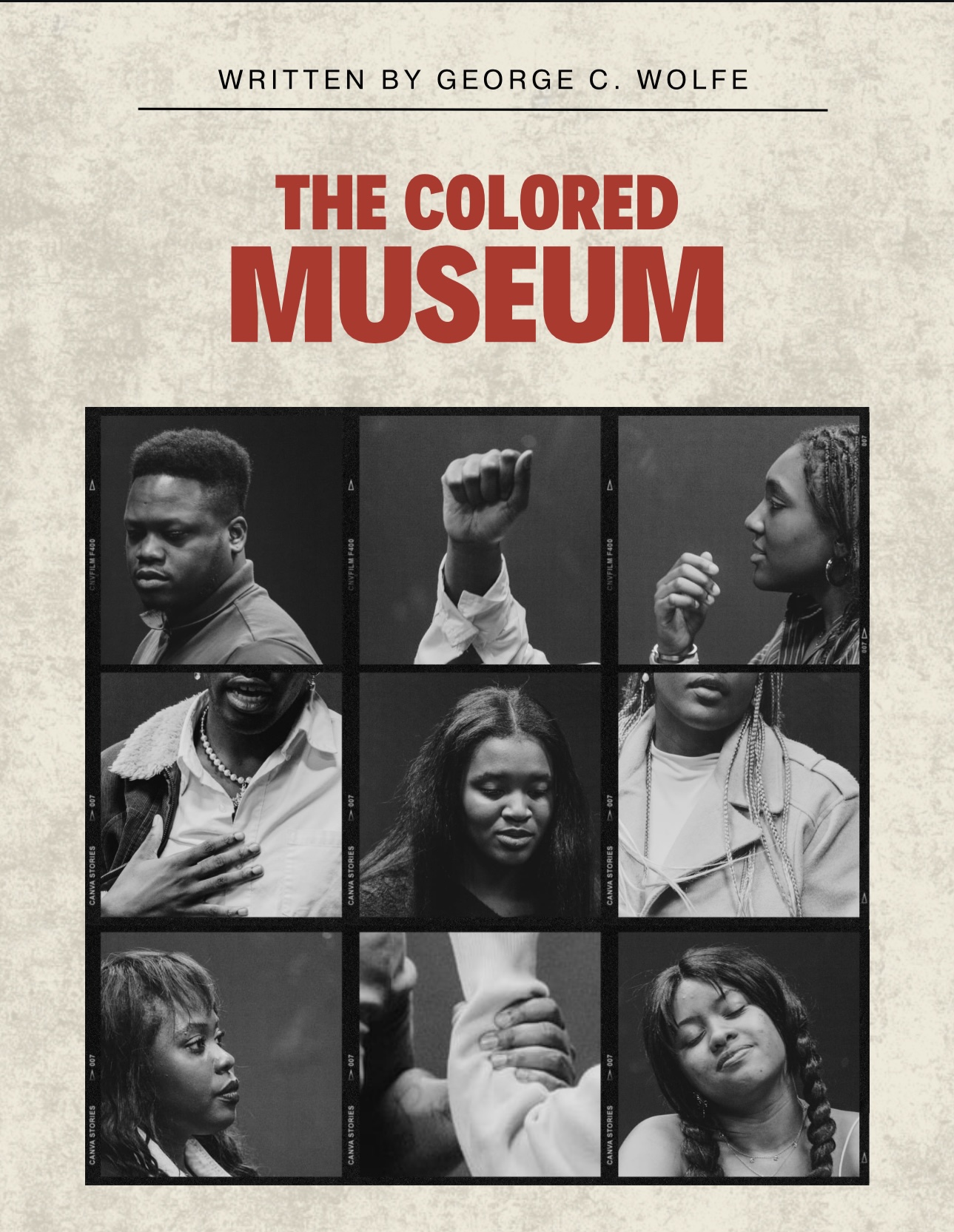

The Black Narrative

Unfortunately, despite Fuller’s work and subsequent recognition of African-American influences in neurology and psychiatry, there remains a racial disparity in the provision of mental health care in the United States. African Americans share a frequency of mental illness similar to that of their White counterparts, yet have reduced access to mental health services and treatments.

Recognition of this inequality is crucial in the present day as the Black and African-American community finds itself disproportionately affected by most of the top diseases. Perceived racial discrimination is associated with adverse mental health outcomes and has intensified since the pandemic. Coupled with suspected racial bias in disease testing, this raises concerns of excess physical morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of mental illness within this community fueling increased demand for services.

What can we do?

Like Fuller, the Black and African-American community can overcome the disparities of today. How? Education is key. Educating the community on health matters can help remove the distrust that many have of the medical profession. At the tips of our fingers, lives a massive amount of information that can help the Black community make choices in health care that will benefit them. The Black community can continue to work with their community leaders and legislation on making healthy food and options available for all. Organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association are leading a charge to get Black Americans to sign up for clinical research, change their lifestyle habits to be healthier and to advance in education, specifically in the areas of health, psychology, and neuroscience. While Fuller didn’t get the recognition he deserved, he showed that even with limitations, success is possible and one can even change the world.